Nadia Piet is the founder of AIxDesign, a global community using AI in their shared pursuit of creativity, justice, and joy. In this interview we explore the communities that exist at the intersection of AI and design, try to untangle what is going on with AI today, and explore strategies for wrestling AI tools and technologies back from the tech bros and bring the AI worlds that we want to see into being.

Margarita Osipian: Could you share a little bit about your own background and what prompted you to launch this platform, AIxDesign, which you founded all the way back in 2018?

Nadia Piet: So I have a super mixed, chaotic background, but mostly in and around design, like UX design, service design, strategy design. Five years ago, I was working a bit more around digital design and data, and emerging technologies was something I was really interested in. But five years ago AI wasn’t like what it is now. It was very industrial, factory based or used for predictive pricing and supply chain optimisation, and all of those very industrial applications.

But philosophically the concept was really interesting—we’re teaching computers to do things. And people started experimenting quite early on with things like sign language and such applications, which I thought was so interesting, But it also felt really far from what I was doing, with things like service design and UX design. I had no idea how these things are going to meet each other. So for my bachelor’s thesis, I made that my question. I questioned how AI and design will intersect. What is a Venn diagram’s overlapping area between those practices and those worlds? So I basically just started doing research and I went down this rabbit hole that I never came out of. It’s just that the rabbit hole has changed a lot in the meantime.

It started by asking what is the role of design and designers in shaping AI to be more of what we want and not of what we don’t want. So rather than leaving those things to engineering teams only, how can we bring this design way of approaching, and making trade-offs, and working collaboratively into AI, to shape that world?

So that’s how I started. Then I created this toolkit, the AIxDesign toolkit, and I just put it online, like, here’s a bunch of shit I learned, maybe it’s helpful for someone. And that got so much response, around 2018 to 2019, and people were like, ‘oh my God, this is great!’ There was a lot of conversation around it. So I decided that maybe these people should talk to each other, and not just to me. I started the community as a Slack group first, and it’s just sort of grown out over the past years, where we started producing content, events, programs, and yeah, just figuring out how to work in this space that we enjoy.

But then 2022 happened and this space exploded. Before, we were doing this really weird, fun, niche thing, or making weird artsy stuff with machine learning. And after, it just exploded and became a really weird, convoluted space. So now we’re thinking, okay, let’s take a step back. We’re not in quite the same place as we were before, just because the environment has changed so much. So I feel like now we are much more on the critical side of things, rather than the fun side of things. And we’re trying to create this literacy push. How can we help more people to have a fundamental understanding of what these things are and how they work, and try to fight some of these myths that are really not helpful, so that more people can have an influence or participate in this, instead of just leaving it to the tech bros.

MO: That was a great introduction! So I was reading that the community is now over 8,000 people, which is really cool, and it’s also self-organised. I was curious to hear about how your community self-organises and also how you link the community to some of the different projects that you’re working on? On your site, you share all these different projects, whether it’s workshops or meet-ups, research that you’re doing. How do you manage this large community with, what seem like, structured projects?

NP: That’s a question I’m working on every day. There are things that we do that work, and there’s a lot of stuff that we don’t have figured out yet and we’re trying to experiment with. Also, the 8,000 depends on what you consider ‘the community’. That is, I would say, the largest scope. But obviously there are smaller levels to how engaged people are and how involved they are, as well as the ways in which they’re involved. Some people have tons of time, but little expertise, like students. They’re very excited, they wanna do work in this space, they have time, but they don’t really know what to do. And then there are people that are really busy, that don’t have time, but they have the influence, or expertise, or even funding from an organisation. So it’s a matter of looking at what different people need and how they can show up, or contribute back to the community, which could be in so many different ways. I’m trying to make a really low barrier to access, but also highly reviewed… we call it the reverse Berghain. Everyone can get in, there’s no door policy, but if you pull one thing, you’re out. So we want to be really welcoming and open, but that doesn’t mean it’s for everyone.

As for the different projects, some of those are self-initiated, meaning I want to do them, so I figure out how to make it happen. Some are member-initiated, which is very often either someone doing something for their PhD, or a student working on their thesis where they want to explore a specific topic and have the community to support that. And some of them are client-driven. Someone we’re now working with is Sublab, where we are exploring how AI shows up in animation and film, and running an arts residency to research that.

So projects come from all different places. A lot of it is open calls, or having open Miro boards or Kinopio boards or open Google docs that everyone can just pop into and contribute to in like, five minutes. But it’s not easy to figure it out and it’s important to question to what extent you can really be self organised, because someone has to facilitate the organisation. I would love to explore being a DAO, for example, and having some of it run through those mechanics. But even then you need someone to initiate, to facilitate, to create their frameworks. So it’s always about finding a balance between self-organised and facilitated.

MO: Those are really important questions about self-organisation and what it means to be ‘open’. This ‘open’ aspect that you mentioned leads into my third question. When you talked earlier about this explosion in AI tools and interest, Open AI is really at the heart of that at this moment. They were originally started as an open source, nonprofit company, as a way to counteract Google and some of these larger tech companies. But I think after two or three years, they became a closed, for-profit company. I was looking at some of the work that you’re doing with AIxDesign and it seems like a lot of tools you’re working with are open source tools. I was wondering about the importance for you, in terms of this work, of using open source tools, and the importance of being open about the research that you’re doing, rather than keeping it closed.

NP: I think we take open source very seriously, but not necessarily with the tools. The research is all open, we try to publish almost everything. Sometimes you do the research, which is a step, and then you synthesise, which is another step, and then you publicise. What we try to do sometimes is to do that all at once. We don’t always have the resources, the time, the funding ourselves to turn something into a nice publication, but then you’re keeping things closed, so we do all of it on an open Miro board instead. It doesn’t look like a publication, it’s literally a super chaotic Miro board with our thoughts, but here it is anyway. We try to do that a lot. And we also share our struggles or what we’re learning as an organisation, with the topics we’re researching.

As for tools, I think it’s nice to have open source ones, but open and closed isn’t necessarily just like good and bad, you know? Sometimes open can also mean unregulated, nobody’s putting any safety and ethics regulations there. At the same time, of course we’re not huge fans of the tech bros, so especially when we spend money on tools, we try not to spend it on them. I love using Google Docs for free, because they’re really open as a collaboration tool. But as soon as we’re paying money for something, I would much rather that money go to a small developer or indie tool teams, rather than the big ones. So it’s definitely something we’re conscious of. And I love this idea of making your own tools, but you need resources to do that. And people can do that in their own time for free, but that means you have another way of paying your bills, so you can do this for fun. It’s not sustainable. Also the maintenance—if you make a tool, you want to keep using it, so someone has to take care of the piece of software.

So rather than us doing that ourselves, which we do sometimes, we like to find them. Kinopio is one of my new favourite things, it’s like a cute Miro…I’m obsessed. And the logo is so fucking cute. It’s like a little melted Tamagotchi guy. It’s also about having tools that feel like nice spaces. And that’s not a Google doc, right? Because you associate that with a specific thing. Or Hugging Face, which is actually slowly crossing over to the dark side. But even just the fact that they have that hugging face emoji as a logo, it just feels different. When we do online community events, we often use Gather, which has a Pokémon on a nineties Game Boy vibe. When people enter that nineties Pokemon Game Boy World space, they’re in the space, in a different way than if they’re on a freaking Zoom, which is an interface that they associate with work, and feels a very different way. So, tools do matter, but are always a bit of a trade off with resources.

MO: And with accessibility. I think even now a lot of open source tools can be quite difficult from an interface design perspective. Some people don’t know how to use them properly. I think etherpad is a really nice example. It doesn’t have all the functionality of a Google Doc, but in terms of note-taking, collective writing, and collecting thoughts in one place, it’s a very easy to use open source tool that you can run on your own server.

NP: And the interface is familiar enough for anyone to get in and not be like, oh my God, what is this, I don’t get it!

MO: And then they get freaked out, and then you also actually end up closed down, in a way.

NP: There’s a real paradox in using a Google Doc. It is obviously the very epitome of what we don’t want, but it is somehow the most open tool, because everyone gets it. Everyone can access it. Using open source DIY tools can actually shut a lot of people out. An interesting friction there.

MO: I’m gonna pivot to a larger question about AI. You talked about this huge explosion that happened, and of course there was also all of this outcry and these fears about these AI tools and these technologies. What I found interesting was that this was coming from people who are experts in the field. There was that letter written by prominent scientists to pause giant AI experiments for 6 months; and then Sam Altman, the founder of OpenAI, making a statement about how these tools need to be governed more; and Geoffrey Hinton, who is one of the pioneers of these large language models, quitting Google over fears about the existential risks of AI. And I was just thinking, what is going on? You work on these things for so long, and then you’re like, oh, oops…it’s almost this Frankenstein idea.

NP: “Oh my God, it’s alive! Now watch it.”

MO: “Actually, now that we kind of went full throttle, without really thinking so much about any ethical implications, we’re gonna just pull back and say, oh, can the government regulate this?”

NP: The people who literally don’t even understand 1% of what you’re doing. It’s like asking your parents to ground you or something. What are you doing?

MO: Yeah. So I was just asking myself, what is happening here? And I’m wondering what your thoughts are on this.

NP: Um, what the fuck is happening? Haha. I mean, it is fucking chaos right now, like a sick reality TV show or something.

I think some of these things are happening because people were really invested in the idea of AI intellectually, philosophically, and technically. Because it is a really interesting question to think about how we can get computers to learn and to reason and to make decisions. We barely understand how our own brains work and this hard and soft problem of consciousness. So I think AI as a field has historically attracted people that are really interested in intellectually, philosophically, and technically interesting questions. Not necessarily social justice people, or workers’ rights advocates, or moms. You know what I mean, people who will come from a more humane, or caring, or feminist perspective. The whole foundation on which this field is developed is those other people. There’s nothing wrong with that, it’s just that that is not the kind of thinking we need right now. Because it’s no longer a speculative, intellectual problem. It’s an actual thing in the world. So we need user researchers and social justice people, the kinds of people that are more used to being on the ground, working through conflict, figuring out what people’s needs are and making trade offs in that.

And then there is the layer of who’s developing these things and why? For what gain? There’s a very clear one way traffic lane towards efficiency and profitability and stakeholder value. But there’s lots of other exits. The AI itself doesn’t give a fuck about making money, because it doesn’t actually care for anything, really. So there’s lots of interesting things we could do, and there’s so much potential there. But most of it is about how we can optimise ad revenue by doing automatic ad placement, optimised by machine learning. And that’s the driver behind so many of this. And this phenomenon reinforces itself: Where does the money go? What does it get better at? And who gets to develop it? And who’s hired into developing it? People who agree with our belief system. So the cycle reinforces itself. And now we’ve just come to a point where it’s becoming painfully clear, the really stark contrast of what is happening. And the people who are super influential in this space, making all the decisions first, they can sense that as well. They’re also in a weird position, where they know they don’t know what to do, but they also don’t really know who to turn to. And Google’s just firing anyone that has a good idea, which is also not great. So I think it’s just those forces, which have nothing to do with AI actually. There was this article that said: the problem with AI is the problem with capitalism. It is just bringing a lot of those issues that have always been present to the surface, magnified under the lens of these new developments. The shit is crumbling, that’s what’s going on, and everyone’s just like, ‘huh’. But it’s just cracking and nobody really knows what to do. Should we just let it fall apart and then try to put back the pieces, or something else?

MO: It’s really exacerbating all of these inequalities and issues around labour that are already in place. It does feel like this breaking point, after these companies have in general just been pushing forward in the name of innovation, without actually having to really think about ethics. When you think about other fields, like for example engineering, if you want to be an engineer that signs off on building documents and drawings, you have to take a very intense ethics course.

NP: And you have individual responsibility in that, not just with your firm. You pledge that you will take this job seriously. And you don’t have anything like that in AI.

MO: No. It is interesting to think about whether this breaking point could also be a push towards a more holistic understanding, like you had just mentioned, where you bring in people from all these other fields who provide another kind of perspective.

NP: Yeah. Whatever it’s doing now, it’s not working. But the question is also, do we try to break that system somehow? What comes after that? This shit is slowly deconstructing itself, but to continue with what we want to construct, should those new people be hired into the tech firms so that it has a slightly more holistic, caring, safe approach? Or should we say, fuck that, we’re gonna build something else over here. Not ask for a seat at the table, just build a new fucking table. Or does this breakpoint really mean that maybe we need to move to different economic models, because this just won’t hold anymore. At what level is it going to change? Is it going to transform the thing that’s there and try to fix it a little bit? Or is it to build something else?

MO: So many important questions!

NP: Yeah. We know we don’t want this. But what do we want? And how do we move towards that?

MO: This is something that I also had in my next question. On the website for AIxDesign, you talk about how you’re redesigning AI for more preferable near futures, which is kind of a start to building our own table. Do we start building the world that we want to see and bringing that into being, rather than trying to insert ourselves? You have a lot of people involved in your work, but a lot of it is still on a small scale, and I was wondering about your thoughts on the importance of the small scale. How does the small scale feed into these larger changes, in terms of actually shaping the communities that we’re a part of, to create this fair, joyful, and inclusive world with these AI tools.

NP: If you are not happy with how things are and you wanna make a change, there’s different pathways you can choose, as an individual or organisation. One is fighting the system, trying to break it or infiltrate. There’s all these archetypes of how to change stuff. Over time, I’ve shifted a bit more towards the path saying, no, just leave that and build something else, for a few reasons that I will try to articulate. Fighting the system, it’s exhausting. It’s frustrating. You hate everyone. Everyone hates you. Lots of people who are advocates like this, they burn out or they become depressed, because you are not in a supportive environment. And instead of actually evolving your thinking, you are just trying to get other people on board to your ideas twenty thoughts ago. So you cannot really evolve your thinking or your ideas, because you’re always lobbying. Which is important, but for so many people that’s also a really exhausting way to live. And then at some point they just opt out, they give up. And you see this not just in tech, but also with climate justice or racial justice. People that are really active in the community and then out of self-preservation, they have to pull out because it’s just too taxing.

So doing these small scale things, it can be really important. But on an individual and small community level it can also be really healing and energising to perform the thing you want to see, rather than just hypothetically thinking about it. And to bump into things and try to resolve them together. You are still working through the topics and the materials and the challenges, but mostly you are in a place where you actually get energy from the work you’re doing, So you can be a better professional thinker and maker, but also a better parent, child, neighbour, because you are not fucking exhausted. Rest is resistance. How can we save the world if we’re fucking burnt out? We probably can’t. To the people who can do that, thank you. But I think for a lot of people who get too demotivated and depressed and exhausted from doing that kind of work, it might be more sustainable and fruitful to do the other work, in which you’re trying to build the alternatives.

MO: And on a much more human scale, as well.

NP: Yeah. Because we’re not made for this scale of the web. We’re not made for the scale at which a lot of these things now are operationalised. So doing it in smaller ways can still be really impactful. I feel like some of our work is sometimes bridging that a little bit. We do this fun community work, but which ideas can we take from that, that also apply in a larger or more commercial context. I think that is maybe the right way to go, for me anyway—back in a space that keeps you working, and building, and thinking.

MO: And energised in a certain way as well.

I have one final question, which kind of links back to your work as a UX designer. How we are situated and our relationship to these AI tools influence how we respond to them, based on the field that we’re in. There’s also people who are not thinking about them at all, one-third of the world’s population doesn’t have access to the internet (that’s almost 3 billion people), which we sometimes forget when we’re thinking about these things. Just situating that, I think that in the field we’re in we’re quite aware about how these tools are infringing on the cultural sector: image generation tools, text generation tools, website development tools. And then of course these fears come up that these tools are going to take away our jobs. But there’s also the argument that these tools could actually open up more space for creativity, because a lot of the stuff that we do is very mundane. We’re doing a lot of robotic tasks. Sometimes you’re just moving stuff in a spreadsheet or summarising things. It’s a really different kind of work. So I was just curious, from your own background and with some of the conversations that you’ve maybe had in your network, what is your feeling about these tools and their impact on creativity as we know it in our field?

NP: For the sake of this question, let’s separate creativity from labour, and then I’ll bring them back together later as the creative industry. If we separate them, I think it’s great. If labour wasn’t necessarily connected in the way it is, AI would just be this incredibly fun tool for creators, where you can, for sure, outsource some of the robotic work, but it’s also a really interesting mirror to work with. People have trained style-GANs on their sketches, or trained GPT models to be the combination of five authors, to then have a conversation with them about this essay they’re writing.1 I think from that point of view, AI is really interesting as co-creation tools, or as a collaborator. I work alone quite a lot, so sometimes it’s nice to share your idea and have the tool be a sounding board in a way. You still obviously need other people for the input, but I think that’s exciting.

As soon as we recouple labor and creativity, it’s a problem. But that’s not because of AI—well obviously it’s making it much worse—but because we rely on jobs to exist. A lot of creativity has been quite formulaic, and that means that a lot of things are now automated tools, to a large extent, which puts people at risk. As soon as it becomes that triangle with labour and our dependency on income, then it is a problem. The writers’ strike is the perfect example, right? Also of how quick this happened. And companies don’t have displacement strategies in place, and are not held accountable for what will happen. And the Netherlands is not the worst place to be, obviously, because we have social welfare and other safety nets, but it’s not gonna be able to catch everyone whose job is essentially perfect to automate.

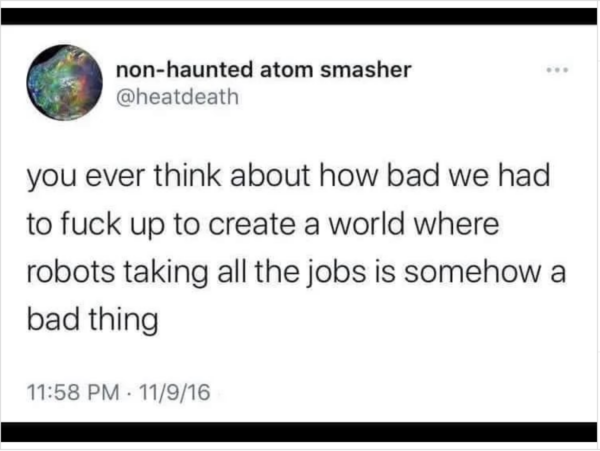

It’s like we’ve been working to make our jobs more robot-like, so that now they can take over. But I saw this thing the other day, saying how much have we fucked ourselves, that the robots taking our jobs is somehow a bad thing? How much have we fucked everything, that that prospect is a fear, not an exciting thing? Because by all means, most people do not like their jobs at all, and they just go because they have to. And even if we do like our jobs, if we didn’t have to do them, we might only do half, you know? We don’t live to work. So what have we done that somehow the robots taking over jobs is a bad thing, which it is.

MO: It’s a bad thing because of the structure that we’re living in. And of course it’s in a long historical trajectory of future speculations about how automation would lower the work week hours, which it has not. And now, people are really afraid. And that’s also because there’s no profit sharing model in place that could then distribute all of this extra productivity that comes with this automation. Because in the end, nobody wants to sit and be a customer service representative at DHL and answer all your questions.

NP: Yeah. So in a way it’s great if a chat bot can do that, and they generally do a better job anyway, because I’m pissed when I contact customer service. Nobody should be the subject of that anger, it’s a perfect job for automating. But someone does actually need that job. And, to your point, it’s also historically a thing, right? We always think AI is going to take jobs, but then it actually makes more jobs. But I do fear for the very near reality of this actually displacing a lot of people.

References

| ↥1 | Artist and researcher Erik Peters speaks about this in this AI Storytelling for Interspecies Futures workshop |