Many of us who grew up with the early internet think back to the days of GeoCities and Myspace with fondness. This was a time where you could create your own unique homepages on platforms, with as many animated stickers as you could imagine, glitter font, and dancing babies. Today, the Big Tech platforms that many of us inhabit online, restrict and limit the forms and ways in which we share content and present ourselves. But can we find ways to use platforms like Google and Instagram, and the tools they offer, in new and creative ways?

To find out, I interviewed Soyun Park, a media artist and designer from South Korea, who is currently based in The Hague. Growing up in Seoul, South Korea, where technological development was rapidly being intertwined with daily life, she found the need to explore her own position in the digital realm. In her work she explores how technology is affecting and changing human discourses from the individual level all the way to politics and communities. Her work takes the form of videos, installations, and audiovisual performances that experiment with a variety of new media and technologies. Soyun is also a founder of a community-based studio RGBdog. I first came across Soyun’s work with the Collective Booklet for Computational Women, a collaborative work she created which is built using Google Sheets. As I began to dig deeper into her projects, I noticed a common thread: Soyun uses a lot of Big Tech tools and platforms in her work. Together we explored what she finds fascinating about these tools, why they’re such a prevalent part of her work, and what her own relationship to Big Tech is.

Margarita Osipian: Where did you come up with the idea for the Collective Booklet for Computational Women project and how did it get started?

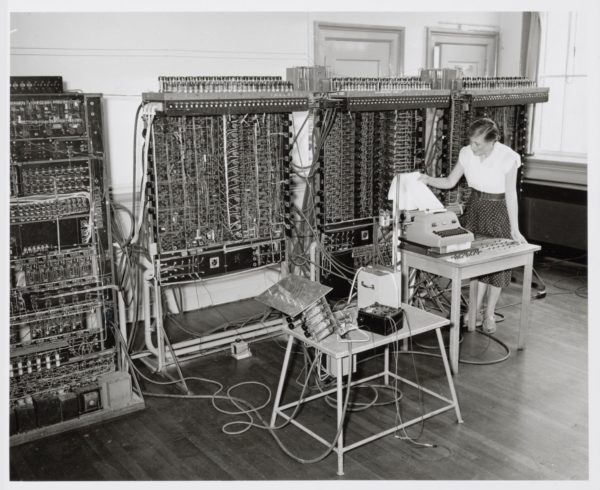

Soyun Park: It goes back to 2019 when, as part of a class at the KABK, we were invited to the International Institute of Social History. Our task was to just find something that fascinates us and research it further. So we searched the archive and I began to search for meta keywords like ‘computer’ or ‘cyber union’ or other words that included digitality in them. And I found this photo of a woman sitting in front of a large machine. And it was intriguing to me. That was the beginning of the project.

So after some research I found out that this large machine was the first Dutch programmable computer, which is called the ARRA (for “Automatische Relais Rekenmachine Amsterdam” or Automatic Relay Calculator Amsterdam in English). Since finding that picture I began to learn that a lot of the early coders were actually women. And that was a huge discovery for me, because I didn’t know that at the time and then I began to find a lot of photos everywhere of these women working with these early computers. I was talking to my friend about my research and she said that we need some kind of space to communicate with other women and talk about our experiences with computers. Because as a woman growing up in South Korea, I always received these comments like “wow, you’re a woman but you’re good with computers”, and it was very discouraging for me to study even something related to computing systems and media art. So indeed I went first to study fine art, which girls are expected to do. So that was the beginning. This one photo led me to create some sort of a space where other women, programmers, can communicate with each other. I think that’s the reason why I also chose to use Google Sheets for this project.

MO: Can you expand on this? Why did you choose to use Google Sheets for this project? You could have used Instagram and asked women to send pictures of themselves working with their computers, but you chose to use Google Sheets. Where did that come from?

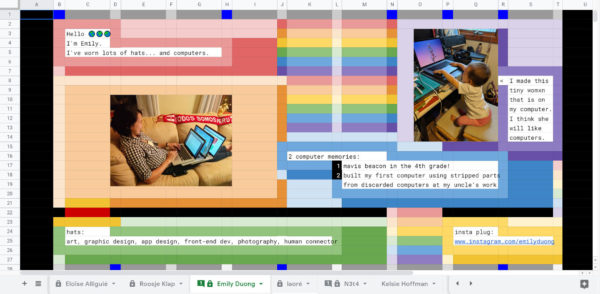

SP: At first, I think it was an intuitive choice. But in the end, I think that I chose it because Google Sheets and Google Docs have such a strong influence on everyone’s daily life. It’s so strong that, if I use them as a medium, they immediately become relevant to the audience. They immediately know that this is a collaborative document, they immediately know that you can change the colour, you can do your own thing on each sheet. And they immediately know that you can also lock it. So it’s been already established in people’s minds how this particular tool is supposed to be used. Although it’s never used in the way that I used it for the project—since it’s mainly used as a data communication tool like an Excel—it becomes relevant immediately and people understand what it is.

MO: That’s such a great point, which I didn’t think about before. When you look at it from an interaction perspective, these mechanisms are already built in and embedded, so you don’t have to tell people how to use the tool. Most of us are using these kinds of tools on an almost daily basis.

For me, this project was really fun to look through and I was always curious what people were putting in the Google Sheets and how they were building their individual pages. I still refresh it sometimes to see if anything new has been added. When you put a project like this out you don’t necessarily know how people are going to respond to it, what they’re going to do. Was there something that surprised you in terms of how people were using the Google Sheets and working with them?

SP: There were multiple cases. I expected that there would be some sort of network developed through the project, with people communicating with one another through it. Especially when people specify where they are from, then people connect more. There was one case that surprised me the most, which was when Roosje Klap (a designer and head of the graphic design department at KABK) started adding people from the project who live in the Netherlands to her social media accounts, as a way to build her local network. There was one sheet showing a woman named Madam Robot, who has a coding cafe and was organising workshops, and Roosje found her via the Google Sheet and invited her to the KABK to give a workshop. I thought it was amazing, because otherwise you would normally invite people you already know, from within your own network. I was so proud of myself for extending this, for expanding someone else’s network in this way. So that was, I think, one of my most proud moments after making the sheets.

I have another similar story, but which involves Google Docs. I gave an online lecture at the City University of New York, and during the workshop I mentioned how community is important in everyone’s development. One of the participants then initiated a Google document to voluntarily add the details of the workshop participants, so that they could connect after the workshop. So there was a list of people’s names and where they live and what they’re interested in—in terms of creative coding, of course. And they just started talking with each other. And I thought “wow”, because it’s like a cool co-documenting system which could be used in so many different ways. And I was amazed at the time as well. Also one of the proudest moments in my life.

MO: It is really amazing to see that. We have all of these tools and platforms built for creating networks, like LinkedIn for example. Then all of a sudden you just have a Google Sheet and it has the potential to become an even stronger way of networking with other people and building communities.

In relation to your work, I was thinking about the Oulipo, the French group of writers and mathematicians whose aim was to create works using constrained writing techniques, like writing poems using only one vowel for example. Because of those restrictions you might actually end up being more creative because you’re working within limitations. What I really liked, going through all of the different computational women sheets, was to see how they were using them, the colours they chose and how everyone was doing something different that also reflected their own personality.

SP: That was also one of the reasons why I chose Google Sheets as well, not the Google Doc, because then you have freedom to create your own room in there. And then you can really see people’s creativity. One person even created a fake monitor in her sheet, and she put herself in the monitor as if you were looking at the monitor. All the cells that make up a sheet are like LEGO, so you can really build something in there.

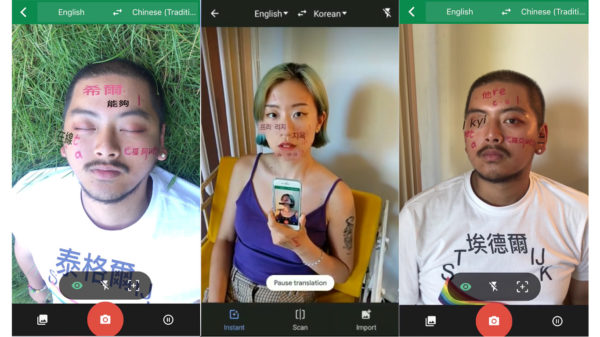

MO: You have another work, Translated Face Filter, that uses another Google product, Google Translate. I understand it as an interface for a performance work. With that work, I wanted to ask you why you wanted to use an already existing tool, instead of building a tool from scratch.

SP: So that work also came out intuitively because I use Google Translate a lot since I moved to the Netherlands, and especially the camera function that it offers. If I get mail from the Belastingdienst (the tax office) then I really have to use the image translation function. With that functionality sometimes the words finish in a way that the machine doesn’t understand, and then it goes to the next row for example. If the words are a little bit far from each other, and if they are in a different shape, then it really messes up the translation. I think I got this idea because I’ve been living outside of South Korea for a long time. When I communicate with people, sometimes I just can’t explain something. It exists in the South Korean language, but it doesn’t exist in English, or exists in Dutch but doesn’t exist in English. So then I have limited emotional or linguistic capacity to express myself to somebody. I began to think that I have lost a lot through that act of translation. I lost myself because some part of myself can only be explained in Korean, but it can’t be the same in English. This feeling was very similar to the act of using Google Translate when you try to use the camera to capture and translate words, it gets lost. Sometimes it even shows completely different words. With this project I wanted to try that out with performative aspects, and I got the chance when I was part of the Ars Electronica festival. I asked festival visitors where they were from, what language they spoke, and if they had anything that they couldn’t express to somebody. Then I wrote what they were unable to express directly on their face with a marker and then tried to translate the text written on their face using Google Translate. So it’s a very bold way of expressing this inability to express themselves. Then, of course, Google translates it and it doesn’t catch the translation completely. So it was almost an ironic performative work, where people could think about which parts of language they couldn’t express.

MO: Your latest work, In the Middle of Attention, which was presented at the Nederland Fotomuseum, is a film made using Instagram. And your graduation work uses Google Maps. You were telling me that you hadn’t explicitly made this connection that so many of your works use these Big Tech tools and platforms, but I was wondering if you have a sense of what’s interesting for you in using these Big Tech tools in your artistic practice as a tool for your work and as a medium.

SP: I put some thought into this question and I think I figured it out. It’s because, in the end, that’s where the data is. So in the end, those are the tools and platforms which have the largest amount of data that I can collect. They are all from these large corporations. Earlier I mentioned that the relevancy of these platforms is very clear to people, because they are so used to using them, and this influences a lot. I’ll tell you the background story of the Nederland Fotomuseum a bit, every year they have an exhibition called ‘Eregalerij van de Nederlandse Fotografie’ which means Gallery of Honor of Dutch Photography. Borrowing the museum’s description: “99 photographs with iconic value which tell the story of photography in the Netherlands from 1841 to the present day are selected by a group of experts”. Therefore, the majority of the photos are selected from their own collection. So what does it mean if your photo is not selected as the honourable Dutch photograph? The curators asked me to question and provoke the idea of the selection and many other photographs which are not selected in this exhibition. Specifically for this work, I wanted to access a large amount of photographs that were not part of the photo museum exhibition and collection. So I searched for instagram photos and videos with hashtags like ‘#dutchphotography’ and ‘#nederlandfotografie’ which are curated by the public. Using a data scraping tool and python I downloaded around 2,000 photographs with the selected hashtags, and then made a humorous and ironic video with them. Using Instagram was a perfect match for what I wanted to say here. There was massive amounts of data in there already, which I could pull from for my project. I think that was the reason to make this sort of work, which needs the data of people, and also points to the relevancy of this current era and digital culture.

MO: In a way, you could say the downside to using these kinds of tools and platforms is that they already come embedded with all of this meaning. What I’ve seen in your work is that you use that embedded meaning for the purpose of the project. I also recognise a lot of what you’re saying about Google Translate, especially for government documents that need translation. All of these kinds of experiences are mediated through these platforms. So I think it’s really interesting how you’re taking all that embedded meaning and really using that to your advantage through the work.

With the research that we do for The Hmm, and the events we organise, we walk this line between being very critical of Big Tech companies and platforms (with their privacy concerns and monopolies) but at the same time we’re also using a lot of their tools. So there’s this kind of tension in the relationship we have to the tools that we use. We ask whether we should be using some of these platforms, like Facebook and Instagram, but at the same time they bring a lot of new audiences to us and help us find interesting people for our own programs. In relation to this, I was wondering about your own relationship to these tools.

SP: It’s almost the same for me, it’s a guilty pleasure. I’m aware of what those large corporations are doing wrong. At the same time, I have a Google Home at home. I talk to Google to turn on my lights and to play Netflix. And, to be honest, it is amazing that I can just turn off my lights from outside. Having a Google Home is really a guilty pleasure. I have three ‘smart bulbs’ at home, and recently I decided to have more normal lamps because digital lamps are expensive. I realised that just getting up and turning off a light switch is not that bad. It sounds a bit funny. But the convenience that they were promoting, the convenience of a ‘smart life’, is not actually needed most of the time. You can just get up and turn off the lights. You can just turn Netflix on, instead of asking Google verbally to do it for you. You can just walk and get lost because you don’t have Google Maps. So I try to just keep thinking that I can be inconvenient and it’s fine. I’m not losing any of my time. But I think it takes some dedication because being convenient is promoted so much that we start to truly believe that being convenient is what defines a ‘smart life’. And I think I should be aware of it. So I’m trying to be fine with being uncomfortable, being inconvenient, and getting confused because I just forgot the way to go home. This digital discourse pushes us so much to have a specific ‘digital lifestyle’, which is of course promoted for capitalistic reasons. But in the end, it’s fine to be inconvenient.

MO: So many of the tools and systems that we use in our daily lives, from private communication to sharing files, are so embedded in our lives and interconnected. I rely so much on my Calendar app on my computer, that if I suddenly lost all of that data I would almost have no memory of what I have planned for the coming weeks. So it can also feel quite dangerous to have so much information that you rely on centralised in this one place.

SP: I am seeing more and more that people are trying to get out of this Google bubble. But since Google is monopolising a lot of platforms like YouTube and Google Drive and Gmail, it takes a lot of effort to get out of that system. Like you said, it’s very dangerous. Once, I think about a month ago, Google completely shut down. Google Drive wasn’t accessible, and neither was email, for many hours. Everyone felt so lost. So what do I do now? It takes consciousness and practice and patience, but I will also slowly try to redistribute my digital memories, to different places, to alternative spaces.

MO: I was wondering if you see the work that you’re doing, as a kind of hacking of these platforms that already exist. We had an interesting conversation about this during The Hmm On the Power of Facebook event that we did a few months ago. One of the speakers was the artist Ben Grosser and he was talking about how it is important to embed his artworks inside of these platforms as a way to get people to think critically about Big Tech platforms, rather than telling people to just get off Facebook, to not use it. For your own work, do you also see it that way?

SP: It doesn’t feel like hacking for me. But I find that it’s very fun and tricky to find another use for a platform then the intended use outlined by the cooperation. And then to see how people react to that, that’s very entertaining for me. I think that it’s really hard to deny the power of these tech companies. Google is terrible, but they are giving a lot of funds to artificial intelligence development in a very creative way. For example, there’s a website where you can quickly listen to all the birds in the world. This data compression process is so well done. It is super quick, there is no delay, and you can even make music out of it with different bird sounds. And these projects are funded by Google. And with Facebook, it’s been great to communicate with people who I will never be able to communicate with after travelling or because I live in a different country. I don’t know how my friends are doing. And then with Instagram Stories, you can know, in a very quick way, what your friends are doing, and you feel connected. So these platforms, on the other hand, are providing a lot of benefits to people. But then how can we be creative with this? That’s my question. How can I introduce some creatives uses of this monopolised social media or Big Tech tools and platforms, because they are intended to be used in a specific way by the audience. So what if I find a different way to use it? A way that you’re not supposed to use it? This invites us to think about this tool or platform again, to ask why we’re using this and how we have been using this and how we could be using it differently in the future. So I think that is my approach because we can’t deny how convenient it is. So what can we do to make it better?

MO: To finish up, could you give us a little sneak peek into your graduation project, which uses Google Maps?

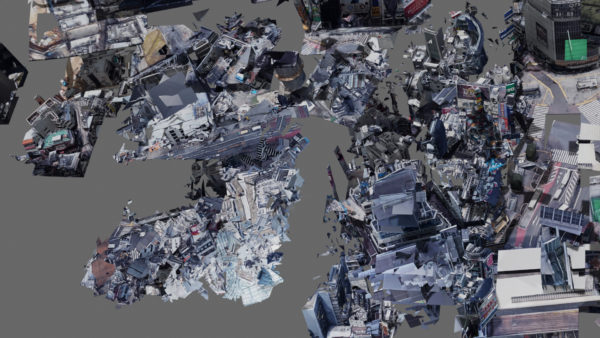

SP: I’m working on a short, experimental fictional film in collaboration with sound artist Inwoo Jung and artist and writer Yerim Ki. Our fascination towards Google Maps started with the idea of photogrammetry, which involves taking photos from many different sides and stitching them together as a texture on top of a 3D mesh. If you look at the Google Maps satellite view, you can see buildings and sceneries in 3D, which are made using photogrammetry. We figured out that with a program called RenderDoc and a Google Maps importer on Github, you can download these maps in 3D meshes and open them up in Blender. Then you can see the 3D models and textures on top, which have the visual information from the map. So working with these 3D models, I wanted to explore the temporariness of Google Maps and the satellite view. Google only updates its satellite views every 1 to 3 years, and so the buildings on the map change very slowly, but this is not reflective of the living characteristics of our environment. The interesting part is that some parts of the world are not accessible through these satellite views. South Korea is not accessible because of security reasons and the relationship between North and South Korea. Up until 2020, Germany had banned Google’s collection of street view images due to privacy concerns. In Wikipedia you can find a long list of countries which you can’t access using Google Maps. It’s fascinating to think about why some parts of the world are not accessible via Google Maps, and some parts are. For my graduation project, inspired by the temporariness of Google Maps, we are making a fictional story about the data of a space and its AI operating system. The story is about a space that used to have a building on it, but then it got moved for some reason. So the physical space itself, the building, is gone. But its digital traces are still left on the map. This project will tell the story of this data ghost.