In March 2020, many governments around the world announced regulations to counter the spread of the Corona virus, in the hope of combatting the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic had started in late 2019 in China but quickly found its way in 2020 to the rest of the world. Almost from the beginning, memes started to circulate stating that “The Corona virus will not last long because it was made in China”. However, the Corona virus proved more durable than the first memes predicted: by February 2020, the pandemic had manifested itself on all continents (except Antarctica).

With the pandemic came an unprecedented surge of pandemic humour: memes, jokes, songs and videos about the Corona virus, the pandemic, the Corona measures and—especially—the lockdown experience. Big events and disasters often lead to a surge of humour, but this particular humour cycle was different. Because so many people were in lockdown, much of everyday communication moved from face-to-face to screen and online platforms. Consequently, almost all of this humour was digital, and most commonly visual, in a form that most people would identify as a “meme”: intertexual, visual, with a distinct cut-and-paste (“bricolage”) aesthetic. The same kind of humour was shared around the world. As people around the world shared similar experiences (e.g., empty supermarkets, locked in at home), they also responded to it in similar ways—and surprisingly often with similar, even exactly the same jokes. These jokes were adapted and translated, and then shared across social media and other platforms. Thus, this global pandemic brought about the first global humour cycle.

In March 2020, we launched a call to collect these jokes. Between March 11 and July 9, 2020, with a group of researchers from 25 countries, we collected 12,337 samples of humour, from 81 different countries. In retrospect, these memes paint an alternative history of the pandemic from a humorous perspective. Because of their digital nature, it was relatively easy to store and create a database of these jokes. Although the timing is somewhat different across countries, we see the same phases around the world. We focused mostly on Europe, since here the pandemic followed more or less the same timeline. In China, we see something similar, but about 6-8 weeks earlier. In Brazil, it came later.

Made in China

The first phase actually proceeded March 2020, as this is the phase of the “the Chinese virus”. Here, the pandemic is ascribed to The Others: it is made in China and will not bother us. This boundary marking includes quite a bit of Anti-Asian xenophobia.

Coronavirus, what a beach

The second phase resembles “normal” disaster humour, from the Titanic jokes of 1918 to exploding Space Shuttles to 9/11: it’s not real. It’s like a movie. In these jokes, a shocking new event is likened to a pop song, a computer game, an advertisement, a film. The memes and jokes of this phase stress the strangeness and fantasy-like quality of this new situation.

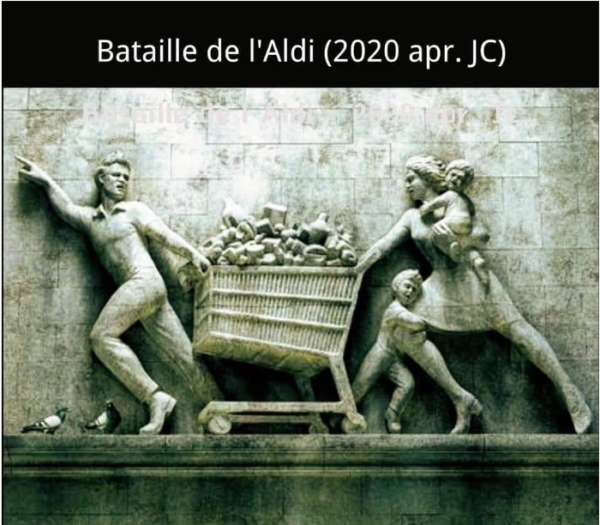

Battle of the Aldi (Supermarket)

The third phase is where things start to “hit home”: The pandemic is here not there, us not them, real not fantasy. This phase is about fear and panic. The symbol of this became the hoarding of toilet paper. This is, of course, a symbol—toilet paper is the pars pro toto for the rush to buy things and prepare oneself for impending shortage and disaster. Panic and fear, expressed through consumption. At the same time, others revel in ridiculing this panic—still trying to keep the disaster at bay by laughing at others.

Couldn’t wash hands. Is now extinct.

Some of the memes reiterated the governments’ advice to listen to the social-distancing rules and follow basis hygiene regulations. Many jokes were being created about sanitary rules and recommendations, such as repeated and lengthy hand-washing.

It’s important to maintain routines

The fourth phase was the longest—roughly from late March to June. These were jokes about quarantine and lockdown. They reflect the difficult adaptation to the new situation—including the struggle to “maintain one’s routines”. This image of a commuter apparently traveling to work was found in many countries, languages, and variations.

It’s day two and my kids broke the TV

In this phase, we see solidarity, as people are coming to grips with the new situation, including working at home with children—a topic of many jokes in our corpus.

A couple of weeks isolation with the family

Besides the frustrations of working at home, apparently people also felt the need to express how fed up they were with having their families around them 24/7.

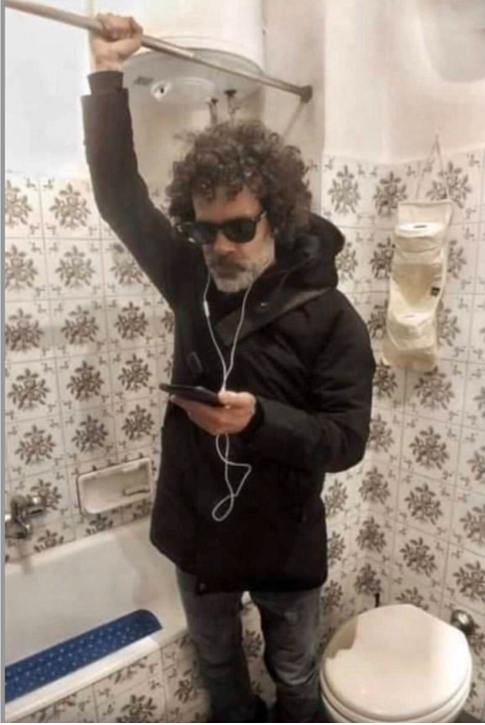

What I thought my apocalypse outfit would look like

And we see boredom and frustration, people frantically looking for things to do, such as walking the dog many times a day, or languishing in their leisurewear.

When you’re laughing at Corona memes

This is lockdown humour, rather than Covid humour. In the jokes overall, there is very little referencing of the illness itself. At the onset, we hypothesised an explosion of black/sick humour at a later phase, but interestingly, this never happened. The coping that people had to do was related to being in lockdown—and not to being ill, or even being afraid of getting ill.

I’m not coming down. Since this morning I’ve gone out twenty times already.

Instead, the coping also is: coping with the measures to prevent the pandemic. These measures were also central to many jokes we found.

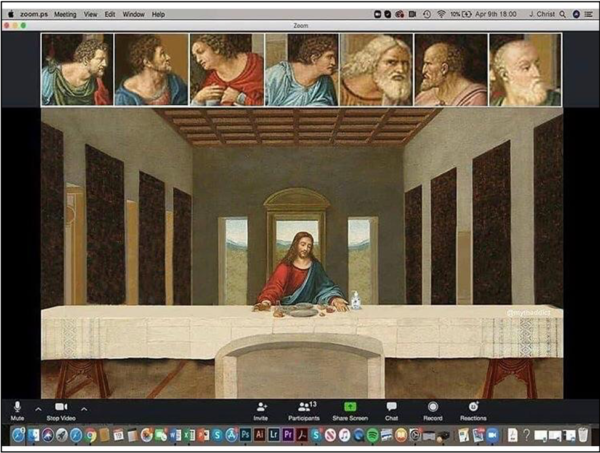

Meme 11: Last supper Zoom

Last supper Zoom

Finally, as the lockdown went on, a fifth phase emerged: as people felt the sense of normality slipping through their fingers, jokes became increasingly absurd. The jokes speak of alienation and isolation as people were locked up in their homes, devoid of human contact beyond their family members—in many countries unable to leave their homes for most of the time.

As this coincided with Easter, we see Christ zooming with his disciplines.

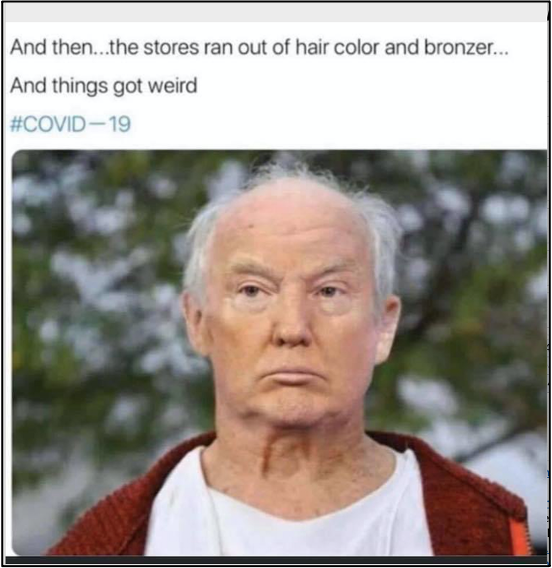

And then the stores ran out of hair colour

Trump—who features in these memes as a sort of global icon and clown—losing his signature hairstyle. Clips of people doing outdoorsy things like cycling in their homes or toasting with themselves in a mirror. All this highlighting—and sharing with the world—in a self-reflexively humorous way the alienation and isolation of lockdown.

Travolta Nighthawks

Culminating in Hopper’s famous bar, without patrons, but with John Travolta–in another meme staple that many of you may know.

Leaked! Rest of 2020 calendar

In June, as the first wave had receded, other events made the headlines—notably the Black Lives Matter protests. The flood of jokes became a trickle, and finally ended. However, what remained was a general sense of doom—again expressed in a meme. By this time, attention had dispersed and the period of strong, undivided global focus was over. And with it, the first global humour cycle.