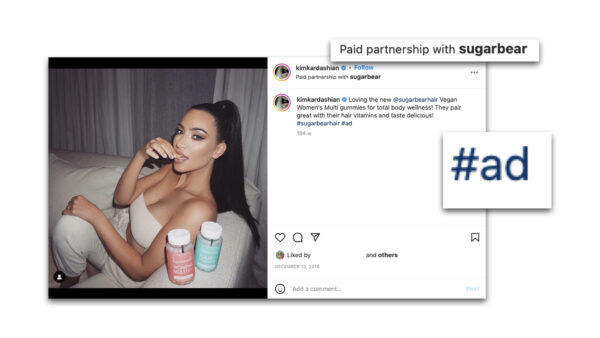

The world of social media marketing is growing increasingly sophisticated, as advertisers figure out how to make their products the most appealing in the least obtrusive way. When this influencer economy was on the rise, we were introduced to it by obviously staged photos, in-your-face product placement, and #ad #sponsored #partner filling up our feeds. However, over the years these ads have become much more refined and subtle, blending into our social media landscape with no problem.

As part of this dossier we hosted a workshop to analyse this process, with Kim Kardashian’s Instagram account as a case study. Instagram is one of the major platforms where the creator economy thrives. One way to monetise your account is to post ads or sponsored content. Over the years this has become very commonplace, as most businesses realise that Instagram is a massive market, with over a billion potential viewers, among them many who cannot be reached by other traditional media anymore. We have all seen these types of posts—the result of an influencer being approached by a brand asking to promote their product in exchange for money or a discount. Sometimes these brands even send their product for free and just hope that the influencer will consider posting about it.

This practice has grown big enough for the FTC (the Federal Trade Commission in the United States) to make very clear rules, specifically for online influencers, that one has to follow when advertising a product. That’s why these posts are often marked as promotional material, or they will have hashtags like #ad or #sponsored. The caption should also make it very clear that this is advertising content. But, according to Truth in Advertising, an organisation that researches false and deceptive advertising, it turns out that over 90% of influencers ignore these rules and this information is disclosed less and less. A brand might only be tagged in the photo, or the ad hashtag is buried away after the ‘read more’ button or in the comment section. One can wonder how disguised an ad can become.

The setting up of this workshop was not easy. Tech companies are becoming stricter in their protection of data, and Instagram is not far behind. As we formulated the structure and work we needed to do to prepare for the workshop, we were restricted by the opportunities we had (or lack of) to scrape the data we needed. The workshop underwent some changes in our goal and process as we figured out what was possible and what wasn’t. When we tried to collect only the promotional posts, we found out that sorting them by hashtags took a lot of effort, especially if different hashtags were used. When we tried to collect posts and captions together, to manually filter the ads, we weren’t able to match the picture to the text automatically (with our limited Python experience anyway). Besides those coding issues, Instagram is notorious for blocking accounts that scrape too much data at once, and newly created accounts don’t get as much access as existing ones. Luckily we were ultimately not blocked by Instagram as we pulled thousands of Instagram posts from their site, but the information we were able to collect was minimal. No metadata was collected in the end, so we were just working with visuals. This just goes to show how shielded these websites have become, and how little we are allowed to know about their inner workings.

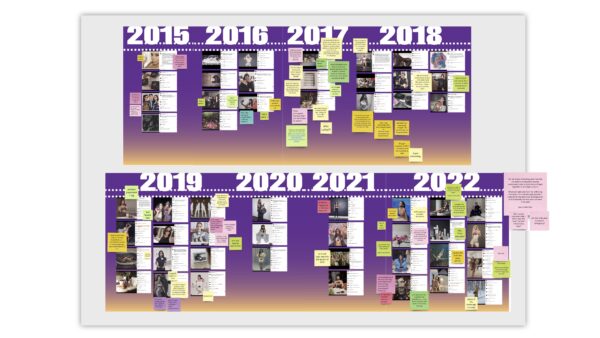

The workshop was divided in two parts. First, we invited the participants to analyse a timeline of some of Kim’s promotional posts, starting from 2015 — the first ad we could find — and ending with her latest Balenciaga campaign shoot. We collected thoughts on these photos from the workshop participants—how they progressed over the years, visual clues on what makes an ad—on post-it notes on our Miro board. It sparked several discussions on the topic, from Yeezy campaign strategies, to staged work-out pictures, to children as an advertising medium. Even after our diligent research, and analysing thousands of pictures, we learned many new things about the Kardashian family.

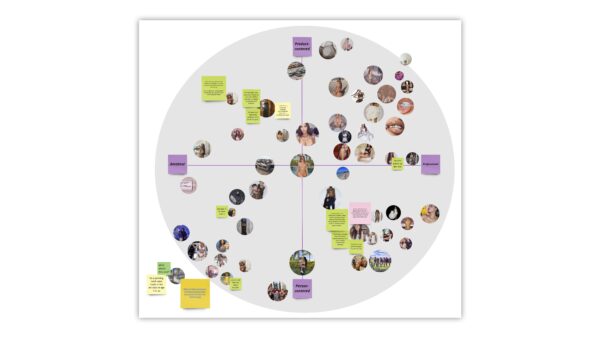

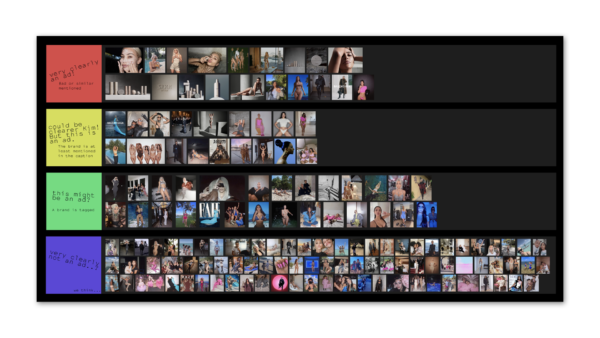

The second challenge was to position Kim’s latest (hundreds of!) posts into a scattergraph depicting her range from advertisement to ordinary post. The horizontal axis was arranged from amateur snapshots to professional photography, the vertical divided the images by type of focus like product or person. The participants commented on the positioning with post-it notes, initiating new, and continuing previous, discussions on the world of advertising and influencing.

It became clear to us that it’s very hard to dissect posts and make conclusions on their “ad-ness”. The Kardashians are especially good at undisclosed advertising. Their Instagram empire is massive, so their reach is astronomical. Oftentimes, they don’t need to even acknowledge the product for it to be bought by thousands. Their fans already recognise the product without needing any additional information, especially when it comes to one of their many personal brands like Kylie Cosmetics or Khloe’s Good American. This is visible on Kim’s Instagram with her own brands SKKN and Skims. She of course promotes her products on Instagram, but the information ranges from actual shop tags and drop times, to just a simple mention, tag, or even nothing at all. She hasn’t used a promotional hashtag in years, but has definitely mentioned many brands. Of course, we don’t know whether she is paid to promote anything anymore, and advertising your own brand does not have clear FTC guidelines. But not disclosing this information makes it very hard to decipher what is an ad and what is just a regular post. This was evidenced during the scraping we did: if there’s no tag to filter by, you have to go through every post manually. But it makes sense that Kim doesn’t disclose anything: everyone already knows her brand after all, how obvious does an ad need to be at that point. It will only make her fans uncomfortable to read #ad in the caption. And the FTC can’t do anything about it if the promotional content is the person herself.

Before the workshop, we compiled a list of Kim’s latest 200-ish posts, analysed them, their caption, and their mentions, and divided them in tiers ranging from a very clear advertisement to what we must assume is a regular post. Comparing it to the scattergraph that was constructed during the workshop, we can see it is very hard to tell an ad from a regular post, despite the visual clues we gathered. When products are this well-known, isn’t every appearance of them an ad on their own? This can also be seen when Kendall is photographed outside a club, with the label of her bottle of 818 tequila strategically facing forward for the paparazzi’s picture. With influencers like this, where their fame reaches far beyond just Instagram, we must question if every post, even every move, might be an ad. And if everything is becoming an ad, how can we formulate guidelines or regulations around these influencers, lest we end up living in a perpetual advertising dystopia? Or are we already there?