‘Influencers,’ ‘content creators,’ ‘bloggers,’ ‘vloggers’ and ‘posters,’ drive traffic to social media platforms. In the interest of not minimising the importance of this digital labour, I will refer to these workers as ‘producers’ in this article. The majority of producers are not compensated by the platforms that profit from their labour or the artistic products they produce. For example, Spotify massively devalues culture by converting music into a DRM-encrypted stream in order to rent access to a time-based entertainment product (similar to the most lucrative digital object: a video game). A fan can listen to hundreds of hours of their favourite album and pay a monthly Spotify subscription while only a small fraction is paid out to the musicians. Artists and cultural producers that keep these platforms alive must seek support outside of the platform to continue their artistic practice. The generating and maintaining of online communities, fandoms, and social groups becomes the key focus of emerging digital art production. Through dedicated audiences, producers are able to crowdsource funding for their project. At the same time, these audiences are valuable attention pools that producers can offer to other producers via collaboration or sell that access to advertisers or brand partnerships. In this way, cultural production begins to mimic the embedded Rentier logic of platform capitalism: Producers see themselves as market makers that drive attention and provide credibility or authenticity to brands desperately trying to access younger hyper-media-savvy audiences. In this article, I will present a series of models that define the digital cultural economy as I see it. These models offer non-exhaustive snapshots of one possibility for how production systems function. They are intuitive ways to think about how capital, attention, and energy moves through online information systems.

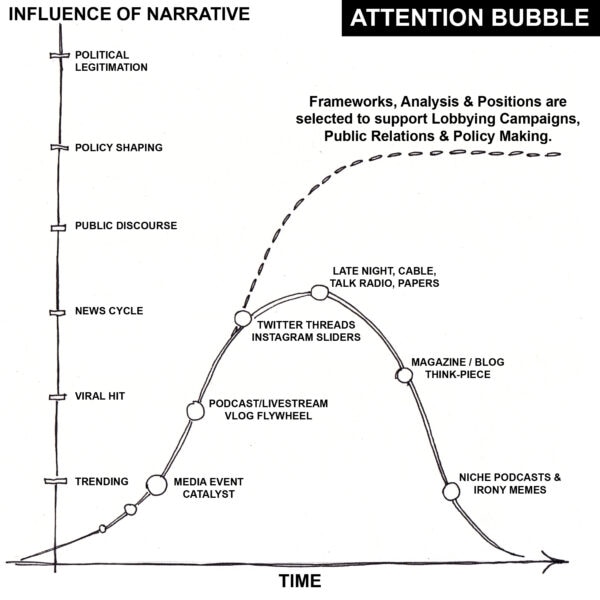

Attention Bubble

Viral news stories follow a pattern of rise and fall through different intensities / frequencies of media. In this model, there are two key points of leverage:

One is at the crest of the bubble; at this moment, well placed narrative flows combined with communities of influence (think tanks, large online collectives) can inject new narratives into the information system. Whereas previously, the media class (editors, writers, owners of media empires) decided what content was circulated, now, viral media contains the possibility for divergent frameworks to take hold.

The second is at the tail end or ‘long tail’ of the attention bubble. After the lights have dimmed and the keyword is no longer trending, there exists a new niche audience that will remain invested in a popular story. These niche audiences can be turned into creator communities by cultural producers if they are able to take up and continue the specific narrative lens of the original viral story. Savvy producers are able to use punditry, analysis, and attention spirals to generate new audiences as each viral story takes off. The breakneck speed and incredible reduction of nuance needed to sustain viral media has created what Joshua Citarella (an artist and cultural producer) describes as ‘the take treadmill’—a trap that producers fall into where commenting on trending stories overtakes any non-viral ambitions. In this way, producers become competitors within massive information markets.

By getting off the ‘take treadmill’, and focusing on core-niche groups of shared interests, producers can create regenerative collective social spaces and new thought. Supporting these new spaces and the cultural outputs of such should be the primary goal of any digital organisation.

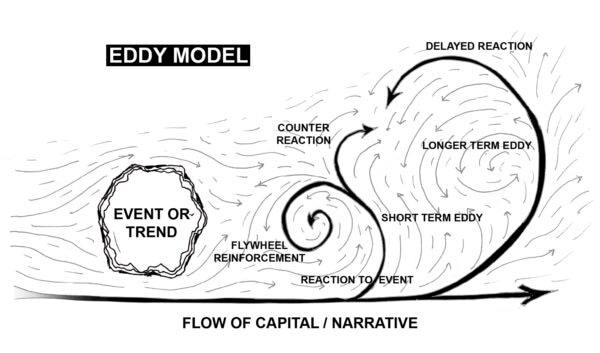

Eddy Model

As producers surf the long tail, moments of friction emerge. These moments are set-off by a specific event or an emerging discourse. Algorithmic curation gives preference to binary political categories. Producers, aware of this dynamic, tend towards presenting a pro or con position on the event or discourse in question. This energy then starts to flywheel into an ‘eddy’—a sustained cycle of refinement where a position is doubled and tripled down. As attention energy is pulled into the eddy, an opposition to this position becomes algorithmically incentivised. As this opposition is then refined and hardened, a third break emerges. Importantly, as the original argument/event moves through slower information systems, the more quickly refined position can come into conflict with positions that emerge later. This creates a strange friction between early adopters and latecomers, who may share many of the same politics but are opposed to a specific wedge issue after getting caught in an eddy.

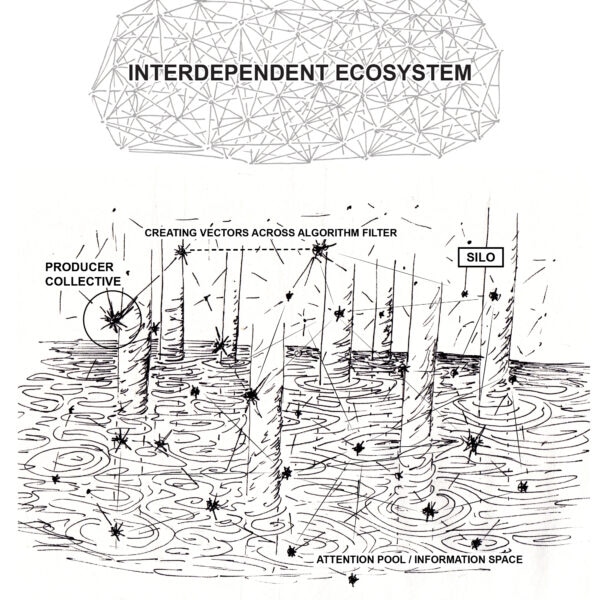

Crossing the Silos – Interdependent Ecosystem

Algorithmic media creates consumer profiles for every user. These profiles are multidimensional and evolve over time as one platform’s data is intersected by another via data markets. As one’s profile refines, they become restricted to specific political, cultural or marketing narratives—referred to as ‘silos’ or ‘filter bubbles’ in popular media. One way producers can generate an audience is by ‘crossing the silo’ in some way, ie. creating a niche experience that connects people throughout the topology of data profiles. By doing this the producer is:

A. Creating a higher resolution sense of self for the audience by modelling an aspect of life un-captured by mass-media targeting / mood-boarding, and

B. Creating a collectivity that cuts across silos—breaking out a curated feed that feels fresh and current for audiences and leads to longer, deeper engagement.

In this model, there exists a counter-competitive dynamic that runs against the platform logic of crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter or Patreon. Unless another producer can generate an audience that is 1×1 identical, there is an incentive to blur the walls between collectives. Accessing larger or different audience pools creates more circulation and stability overall for producers. Rather than competing with peers for subscribers, an interdependent ecosystem of producer collectives can emerge. Thus, taking on a similar shape to that of the highly collaborative music industry, with bands playing bills together to expose new acts to audiences.

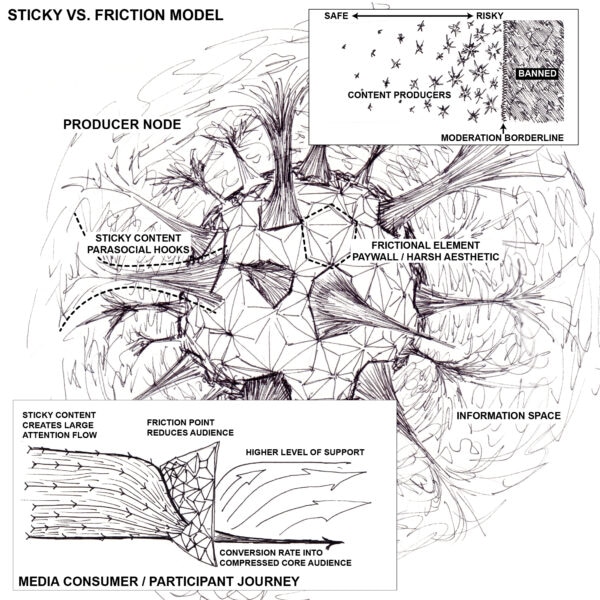

Sticky vs. Friction model

Social Media derives profits from generating ‘sticky’ content. This is content that drives inbound engagement (shares via dm, word-of-mouth, news media stories)—bringing people onto the platform to experience a piece of new media firsthand. Producers that can generate a heightened emotional state are rewarded with more algorithmic attention. ‘Organic’ viral moments are catalysed when charged imagery is combined with positive algorithmic feedback. Content is pushed to the top over and over again when consumers trigger algorithmic preference by spending extra time with content, leaving comments, sharing to others, or debating on Twitter. If media start to cover the story the moment can snowball leading to new video reviews, memes, and podcasts created to analyse further. Whether it is Kim K ‘breaking the internet’ with a provocative photoshoot, or video documentation of a police officer committing homicide, the social media algorithms boost ‘sticky’ content to satisfy the demands of profit: time spent on platform and exposure to advertising.

While modern web design aims to reduce any and all friction (seamless gradients, easy clear UI, limited choices) in order to best serve commerce and circulation of information, organic viral content requires a certain level of friction in order to transcend its niche origin and make it out into a broader content pool. The frictional element makes the content harder to access, therefore requiring more buy-in on the part of the gawker. Examples are:

an actual paywall, obscure website, aggressive meme aesthetics, longform (hour 2 of a podcast or livestream), pornographic content, offensive language, slang or vernacular.

While platforms demand ‘sticky’ content from producers, the frictional element needed to succeed on the market often pushes the limits of social media content moderation. This censorship dynamic makes making a living as a small producer (50k-250k) a difficult tightrope walk. A producer must weigh the benefit of generating a larger audience with edgier ‘borderline’ content vs. the risk of getting ‘shadowbanned’ (deboosted or deprioritised) or completely deplatformed. Crucially, the Sticky vs. Friction model works to centralise political power around the support of the platform: calls to stop the censorship of borderline content amount to pleading for the ability to generate free revenue for private companies.

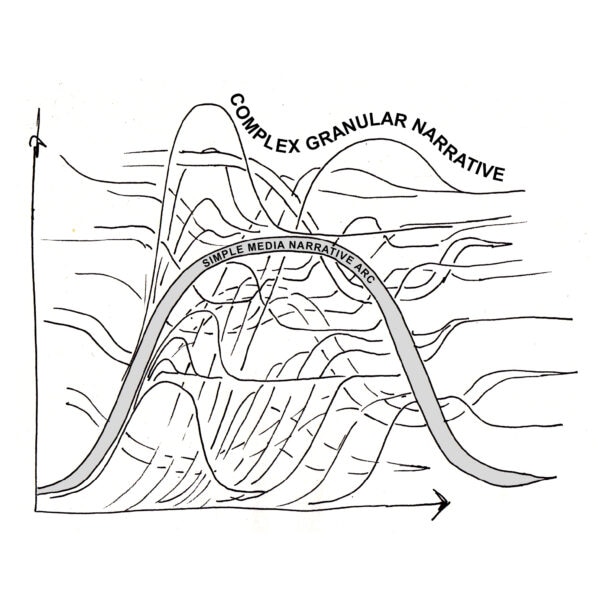

Granular Narratives Model

Viral media works at many scales. A post with 5 likes is just as subject to incentives, predesigned outcomes, and attention bubbles as content with 50 million impressions. In order to fully capture a viral story, a journalist must work at many scales at once. The local, regional and global are all collapsed into different stages of a story’s viral wave. Each time a story escalates previously aware audiences then refract and complexify their understanding. The granularity of any given story provides intrigue for media critique, where we often hear things like “I am more interested in the response to the movie than the actual movie.”

Even more often, lazy internet journalism provides little context or sense of time and scale when presenting a viral moment. The framing centres the virality itself—the fact the headline is trending on Twitter is the subject of the story. This self-validation of a story’s worthiness create negative incentive for entertainment celebrities contracted to promote products: get trending in order to get press. Using a more nuanced, granular approach to narrativising what happens online, viral media reporting can become more legitimate as a form of storytelling, and less trapped by quickly forgotten news-cycles.