About a decade ago I was a somewhat active member of the Kanye West fan forum KanyeToThe.com, often abbreviated to KTT. Having discovered the rapper as a teenager, exploring his discography and impact on contemporary culture was exciting to me. Finding an online community that shared that same enthusiasm was even more so. Here I found people sharing their interpretation of his music, the latest updates on his projects and leaked songs and videos. Unfortunately, there were also many people on there who might have been a little too enthusiastic and careless, and even some downright trolls. I vividly remember at one point, when someone started a thread with an extremely dumb or naive idea, “let’s do…”, I was one of the first people to reply with a simple “let’s not”. What happened next was that many other members started to quote my post without adding a response, basically echoing my statement. I’m not sure if I felt bad for the OP at the time or if I was surprised by the massive response I got, but I definitely do remember the rush of gaining social status, clout if you will, on the forum. It might have been my first time, of luckily just a few, participating in toxic stan 1 behaviour, though it was only limited to in-fighting. I haven’t logged into my account for years now, but The KanyeToThe forum is still online and has people posting daily. For some reason a second website KTT2 was started. The two exist in parallel and whenever I need a link to a leak or a mirror of a stream of a new Kanye project I go there as an unregistered visitor.2

Of course, my adventures on KTT are just a small blip of what online fandom consists of today. In the years since I last logged in on the forum many things have changed or accelerated. Online fans seem more present than ever. The most die-hard ones being called stans, a term they were first mockingly called but now often carry with pride. The act of engaging in stan activities has become a verb: stanning. Armies of stans now engage on a daily basis on the battlefields that are Twitter, Spotify, iTunes, and other social media platforms, streaming services, and stores, to fight for their idol, as well as themselves and their community. In this essay I will try to map out what online fandom actually consists of and why it’s now bigger than ever.

In the book Transmedia (2013) by Dan Hassler-Forest, it becomes clear that online fans, right after the arrival of the internet in the US, began to impact the entertainment industry. Dan writes about the website Ain’t It Cool News, run by film fanatic Harry Knowles, who enthusiastically posted rumours and news he found in Usenet groups about films and later from insiders in the industry. The site played a big part in the lacklustre public perception of Batman & Robin as negative reviews from an authentic fan like Knowles coloured later reporting by professional journalists and critics.

Then years later, Web 2.0 came around with early social media networks such as Myspace, which centred around music and where fans had new ways to directly get in contact with the artists they admired. Some artists who became popular on this platform, like Arctic Monkeys, got offered record deals from labels and have since started careers to varying degrees of success.

On Myspace, fans would just gather on the page of their idol and leave others alone, but as time went on, and new platforms emerged, this changed. On Twitter there are no groups or pages you can post to. When you search for certain words or hashtags you can find all public tweets mentioning them. This causes way more interaction between strangers and, in the case of stans, leads to more rivalry among different stan groups. So instead of staying within their own community, stans of one artist started to aggressively respond to tweets from stans of different artists. The part of Twitter where these exchanges take place has been dubbed “Stan Twitter”. It is the birthplace of many memes and online slang, but is also infamous for bringing out the worst in people, such as harassment campaigns and death threats. It even has its own Wikipedia page explaining the phenomenon in more detail.

Sometimes, certain fan groups favour specific platforms. Taylor Swift, for instance, likes using Tumblr, so her fans—the Swifties—will also go on there in the hope that they might get some form of contact with her. And in the last few years, artists like Arca and Grimes have started their own Discord servers. Here, they talk directly with their most dedicated fans, as these spaces often have less users than, for instance, their Instagram accounts have followers. Other times, artists actually take advantage of their massively followed accounts to make sure all the fans get their message. For example, when Nicki Minaj had to tame her Barbz on Instagram Live, or when Taylor Swift sent her stans after Scooter Braun over a conflict about her master recordings.

For me, early social media networks—in my case the Dutch platform Hyves—also mark something else: the beginning of the (online) personal brand. In my view, millennials who grew up with these online platforms are used to presenting themselves online not only as their own personal brand, but also through other brands. On Facebook you could like Pages created for film franchises, bands, tv shows, fashion, or product brands. Liking certain pages on Facebook was not just to stay up to date with them, but also to have them be part of your profile. On Hyves, the brands you ‘respected’ were even listed in your profile info right on the top of your profile page. This synergy between brand and person—where the brand is part of you and you are part of the brand—does not only seem like a precursor to Instagram, where you are basically presenting and shaping yourself as a brand, but also shows a similarity with how online fandom functions these days. When stans of a specific artist put in effort to get their artist’s new single to the top of the charts it is not only a victory for the artist when they succeed, it’s a win for their entire community. Similar to how supporters of sports clubs can get excited over a championship win, it makes the stans feel like—or even proves to them—they are on the winning team. Exemplary of this is the @chartdata Twitter account, a bot that posts all kinds of facts and statistics about music charts and streaming numbers, which many stans then retweet, celebrate, and brag about.

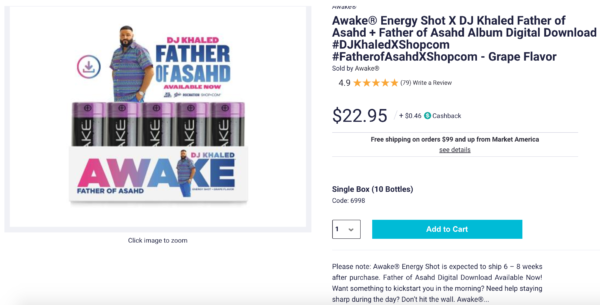

What also adds to this ‘music as a competition’ idea is the fact that, in the age of streaming and social media, tons of statistics are available. Besides the more well known charts that combine radio play, sold copies of songs, and streaming numbers, new kinds of specific statistics can be tracked which open up space for new records to be set. This means that stans can both hype each other up to stream a song to the number one spot on the Billboard chart, but also care about more arbitrary records like the most views within the first 24 hours for a music video on YouTube. Music labels tend to play into this, as they obviously profit off of the streams and sales of their artists. In recent years, a useful way to sell more copies of an album has been to bundle it with merchandise. This started out with getting a download link for a digital copy of an album when purchasing a shirt or hoodie, but after a while the merchandise became more disposable and just an excuse to pump album sales. Ultimately this led to Billboard changing the way it counts album sales, especially after DJ Khaled sold a copy of his album with an energy drink as a merch bundle in 2019—one album per can. Slogans literally said “buy a 12 pack to push DJ Khaled to no.1!”

Another place in the music industry where numbers-obsessed stans have shaken things up is criticism. The website metacritic.com collects all reviews for films, games, series, and albums, and then gives them an average rating based on the reviews they’ve collected. It also shows what media outlets gave which ratings. Even when the initial review does not contain a score or a number of stars, the sentiment of the review gets converted by the site to a numerical rating. For some stans, a critic not giving their idol a perfect score is enough reason to go to war and deploy some harassment tactics that seem to be taken from the Gamergate playbook. All available contact information of the critic and their employer will be dug up by, and spread among, fans to blow up their phones and inboxes. Needless to say that tweet storms are part of the treatment as well. Last year, when New York Times pop critic Jon Caramanica—whose podcast Popcast definitely helped shape my research—wrote a, not even that negative, review of Taylor Swift’s Folklore he received hex tweets from Swifties for days, if not weeks. A prime example of Stan Twitter.

Of course subcultures already existed before the internet, and music and films were ways for people to form and express their identities for decades. But the amount of people actively participating in fandom, and subsequently the acceptance thereof, seems to have grown massively now that fandom has moved online. Whereas in the last decades of the 20th century a select group of die-hard science-fiction fans created a participatory culture around certain movie franchises, comic books, and other media3, nowadays millions of people around the world participate in fan behaviour. As a result, not all fandoms are perceived as nerdy or geeky anymore. This is definitely visible as the older members of the millennial generation are entering their mid-30’s and still walk around with Deathly Hallows symbol tattoos. Or even worse, become Disney adults.

But it is not just that the internet has redefined the way the entertainment industry works and has helped make fandom a part of more people’s lives. The tactics and methodologies of online fans are actually being adopted outside of the entertainment industry as well. A prime example being the campaigns for the 2020 US Democratic Party presidential primaries. Whereas in 2016 the term “Bernie Bros” seemed to arise somewhat organically—though not as a cool nickname, but more of an attempt to frame Sanders’ supporters as sexist—last year Kamala Harris’s campaign team took it upon themselves to name her following the KHive (after one the biggest stan armies of all, Beyoncé’s BeyHive). A while ago I was looking for BeyHive GIFs to add to my Instagram Story (this was for research purposes, I do not stan Queen Bey). To my surprise, all the way at the bottom (presumably because no one actually uses them when looking for BeyHive GIFs) there were a bunch of KHive images I could choose to add. Closer to home, during the Dutch elections this year, the online campaign #TeamKaag was set up to promote D66 candidate Sigrid Kaag and ran alongside the general campaign of the party. The campaign completely focused on the persona of Kaag. The #TeamKaag campaign claimed to be a grassroots movement and not part of D66. The truth was only revealed in the privacy policy on their website, which referenced the party a number of times. It mentioned, for instance, how “D66 does not save personal data any longer than necessary.”

Of course, in this essay I haven’t been able to give a complete overview of everything that can be considered online fandom. I haven’t touched upon the communities surrounding manga and anime, fans of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and other film fanatics, K-pop stans whose community has grown massively over the past decade, or the endless amounts of fan fiction that’s being written across different fan communities (did you know 50 Shades of Grey started out as a Twilight fanfic?). And I’m sure there are fans in corners of the internet I don’t even know the existence of (yet). What I’m certain of though is that social media platforms, their users who participate in fandoms of many varieties, and media conglomerates such as music labels and film studios have been affecting each other over the past decades and the interplay, codependence, and tension between them will most likely only continue to grow.

References

| ↥1 | A term for die-hard fans, named after the Eminem song. |

| ↥2 | A mirror of a livestream in this case would be a livestream on a public platform that is showing the footage of a livestream that is paywalled or otherwise made exclusive. |

| ↥3 | Described in chapter 2 of Transmedia by Dan Hassler-Forest, Amsterdam University Press, 2013. |