PREFACE: Move too fast and you will end up shaving your head bestie…

In 2010, the legendary Miss Britney Spears released one of her many-to-come fragrances, named Radiance. I’ve never had the chance to buy or even try it, but the video commercial for its promo lives rent-free in my mind since its release.

A radiant Britney cleverly avoids the paparazzi waiting for her to exit a function, successfully leaving from the back door without anyone noticing. Looking and feeling ethereal, she roams freely around the city. Suddenly, she stumbles upon the window front of a fortune teller’s shop. She gazes inside, intrigued, and proceeds to enter. Pushing aside a Swarovski curtain—a burgeoning reminder of late ’00s and early ’10s aesthetics—she’s greeted by the fortune teller, who urges her to approach:

“Please… Do you want me to tell you your future?”

The voice is lulling, orchestrally moving hands above her crystal ball. Fluorescent lights within the ball begin to spin quickly—quicker, at least, than the pace of the rest of the commercial. Even Britney moves slow throughout the whole sequence.

At first, Britney’s gaze drifts into the swirling crystal ball. And yes, I have to admit: the quick pace of the lights—even though they are not the central subject of the frame—is mesmerising. But before the fortune teller even attempts her reading, Britney slowly yet firmly walks out of the shop. Her reply to the question is as steady and deliberate as her exit:

“No thanks. I choose my own destiny.”

Ok bestie… can a girl in this atrocious world live in peace and slow down?

The way I experience girlhood in our current chronology is a constant fight against an accelerating system. For years—right and lately left—we’ve been hearing big promises about Accelerationism. The Girls have been its victims too: we were forced to passively Girlmaxxx, to accelerate our cuteness. But for whom? And how? Is this a desperate attempt to complete the Girl and drive her out of existence?

As Alex Quicho astutely describes in her Girl Theory, “[The girl] is in a constant process of becoming.” To many, this process is known and deeply embedded in everyday life. The Girl does transform, but here I want to argue: she does so at her own pace—not in a post-human, post-apocalyptic, and definitely not a Nick Land-ish, fascist type of way.

Right now, I feel—more than ever—that the Girl, us, every marginalised community, are like Britney and the paparazzi in the ’00s-’10s: ballast for a white, manly, ever-knowing, and fast gaze. Performing under this gaze, even if we write books and theory, aestheticising the process, we are mathematically driven to collapse. We become Britney in the hair salon, shaving her head. Lost in time. Lost in a process so fast we cannot even think.

1. Lost in an image, in a dream

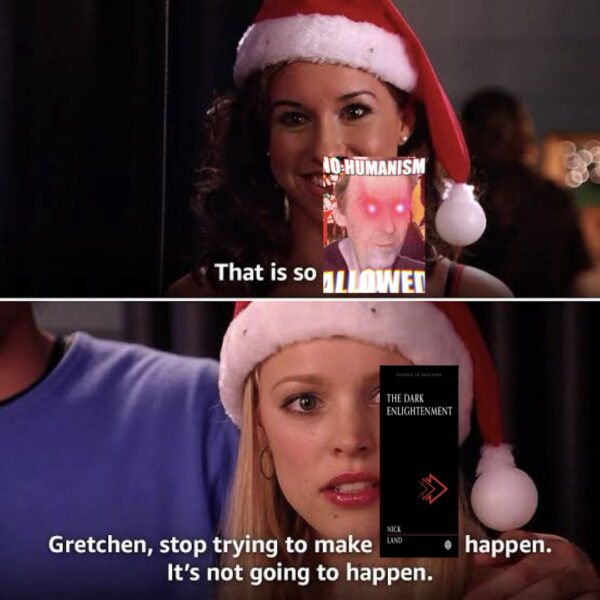

Get in loser, we are debunking bad boy Nick Land in this chapter.

I know many claim to be “not-like-other-accelerationists”—this is very pick-me of you, besties, but all accs are traced back to Nick Land. Everyone acted brand new when Jonathan Derbyshire posted his article, “The philosophy behind Trump’s Dark Enlightenment: An English magus of anti-democratic neoreaction has become a touchstone for the alt-right.”

The article shows how neoreactionary accelerationism, via thinkers like Nick Land and Curtis Yarvin, influenced Trump-era politics. Their vision replaces democracy with CEO-style governance, aligning with efforts to dismantle state institutions. Once a fringe philosophy, this techno-authoritarian logic now echoes in Trump’s agenda and Silicon Valley libertarianism. After all, if “left”-accelerationism is so good, then—to quote Britney yet again—“why do these tears come at night?”

The left’s fascination with acc seems to me a clear indicator of pick-me behaviour. It’s the same fascination that drove pick-me girlies back in the day to despise pop and girly culture, blasting boy-core music on their speakers, craving to be one of the boys. And no offence, angels—I had my fair share of pick-me attitude, but those days are (thankfully) long gone.

The only good thing about forcing yourself to like music that appealed to your older brother’s best friend? It carefully resulted in the impeccable taste that later transformed into girl-core during the early Tumblr days. So yes, this is character development that was actually fun.

On the other hand, can we please stop trynna make any form of acc happen? It’s not gonna happen—and if it does, we’ll be long gone.

2. Not a Girl, not yet post-human

The hard-niche internet girlies have been fascinated these last few years with a new form of acceleration. Like all the makeup trends we followed—only to later realise we were scammed—it promised to help us understand the poetics of cuteness and how its metaphor might usher us into questioning gender.

And although Cute/Acc made a really cute attempt (all puns intended), it missed many marks by making its first lethal mistake.

It’s true: with the rise of all these internet aesthetics and their mix-and-match chaos, we aim to bring clarity to a system driven by capitalism. The vastness of content is similar to what, in another age and time, would be called the Sublime. The fear one might feel staring into an infinite, angry Romanticism painting mirrors the solitude, fatigue, and confusion we feel when bombarded with content—without even a moment to comprehend it.

But what I’m curious about is the merging of elitist academic chaos with the capitalist one. How is it valuable to make each and every “Barbie” kiss each other? The Deleuzian Barbie kissing the Kawaii one. Will the Kawaii Barbie be more valid this way? Or is it just another rabbit hole: experiencing [insert literally whatever] through the lens of capitalism and Big Daddy?

Is cuteness only allowed to be valid because it’s experienced by the communities that claimed it before the ever-curious academic eye? Is cuteness hotter if it sits side-by-side with Deleuze and Guattari, introducing us to their newly found throuple situationship no one asked for but a curious few fans requested?

At its core, cute/acc shares the anti-humanist drive of Landian accelerationism: gleefully surrendering to “desubjectivising flows” and the post-human techno-future. But this isn’t subversive—it’s profoundly privileged.

To embrace anti-humanism while inhabiting the unmarked space of whiteness, techno-comfort, and cis-structural safety is to erase the fact that many identities—Black, queer, trans, disabled, racialised, precarious—are still denied basic humanity. For those still struggling to be seen, heard, and protected as human, the fantasy of dissolving the human isn’t liberatory. It’s violent.

Cute/acc makes no attempt to reckon with this. Its love of regression (“acceleration = regression”), of becoming object or neotenised commodity-self, mirrors neoliberal affect markets perfectly. It aestheticises surrender while the techno-authoritarian machine advances. When theory tells us it’s cute to regress into objects, it erases the fact that some of us are still fighting to be seen as human.

Where opacity (Glissant & Nelly Y. Pinkrah) is a refusal of violent transparency, and where hauntology (Fisher) slows time to make memory and care possible, cute/acc embraces dissolution—and in doing so, aligns itself, willingly or not, with the same necropolitical drives that have always underpinned fascist acc.

The Girl can choose her destiny. Or she can be flattened into it.

3. Every time I try to fly… I fall (and dance in my own living room holding two knives)

This part of the text was really hard and took a toll on me the last few months. I was constantly writing and erasing ideas. I am consciously changing the mood and the writing style because I can’t find words to move into slowness as a concept. Like Britney in her iconic superluminal video for the song “Everytime” I find myself running across the corridors of my mind in a Sisyphean attempt to break out of the speed of system that every day I realise how numb and anxious it makes me.

Originally, I wanted to stress out a big idea around slowness as a concept, but to be honest I have no big words for it. I am currently still exploring it, still immersing into it. Sometimes I find it easy with the help of various art and media that I am gonna present later on, other times I am still angry at time as a concept. I am angry because I can’t seem to understand its pace, and I am angry with all the edge-lord shit of acc for the same reason. To tie it in to the theme of this publication, its myself. It’s myself most of the times that I’m being mean to. That is when the guilt of time that moves faster than I can fathom kicks in. So maybe I might as well slow down.

4. Move slow… there’s just things about (us/me) you just have to know

Tung-Hui Hu’s Digital Lethargy examines the exhaustion, numbness, and passive states produced by life under digital capitalism, where users are framed as endlessly productive yet often feel drained and slowed down. Instead of pathologising this lethargy, Hu suggests it can hold resistant potential, a refusal of acceleration and efficiency demanded by platforms and algorithms.

What stays with me most is his postscript. He writes about waiting—not as dead time, but as a kind of intimacy. The way we all touch the same cardboard boxes, the way insomniacs unknowingly keep each other company through the electric green wash of screens at night. He reminds us that lethargy is not an end, not a failure, but a shared condition. It is the quiet company of those who are told to “look alive” even as the world itself is collapsing.

Reading this, I recognise my own rhythms: the guilt of moving too slow, the shame of being unproductive, the ache of feeling late. But Hu reframes that lag as something numerous, something collective. Lethargy is not just mine. It is a way of being with others, a small refusal to let speed define what counts as human. Maybe slowing down is not heroic, maybe it’s not even intentional—but it is what allows us to cleave to the world, bitter as it is, and still endure.

5. Gimme more!

Although I have to admit a failed attempt to write theory about slowness (for now), I want to dive deeper into media and theory that owned my whole body and soul the last few months during my not so successful attempt to map slowness as a concept.

The rabbit hole down Tung-Hui Hu’s “Digital Lethargy”, drove me once again to the uncanny neighbourhood of Mark Fisher, to the slow cancellation of time, to liminal spaces and the backrooms. And honestly, don’t send help, because I am starting to feel kinda cozy here.

Mark Fisher through his talk “The Slow cancellation of the future”, that was hosted at MaMa at Zagreb back in 2014 (Triassic period in internet years), argues that culture no longer produces a discernible present or future. And even though my dark soul agrees with that argument, I can’t help but point out that we are driven yet again to think of another binary. A future that is cancelled and a past that eternally loops intoxicating the present, and I am certain I am not happy and pleased with that argument. The way I am trying to make the two Barbies (Fisher and Tung-Hui Hu) kiss is because I believe that there is also a true sense in sitting with the silence and stagnant present as it is for a bit. Maybe as Hu stresses it is the only liberating moment we have, the coziness of a ghost time and space. Maybe there is where hope is birthed. Maybe within the liberation of stagnation we can feel again boredom instead of anxiety and then we get something new—to invert the fears that Mark Fisher astutely pointed out during “The Slow cancellation of the future” that is my new Roman Empire.

Epilogue: Hold Me Closer Tiny Dancer (and then let me slowly drift away)

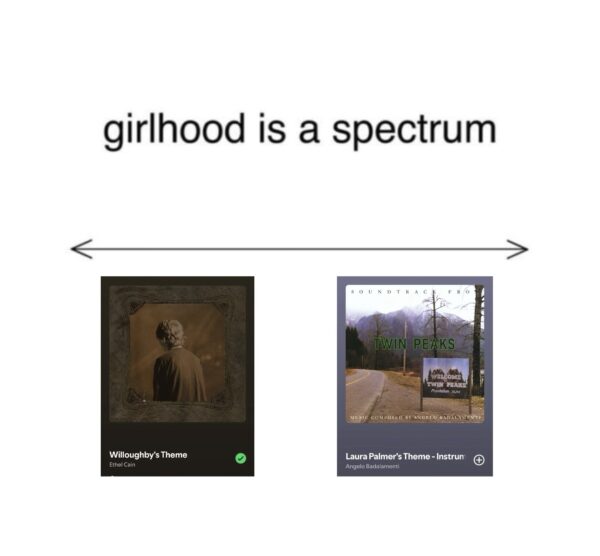

I started to obsess over Ethel Cain last year. Her music moved with a weight and patience that unsettled me, but it wasn’t until January, when Perverts was released, that I fell in completely. The album didn’t just sound beautiful—it sounded suspended, stretched out, unwilling to hurry toward its own resolution. Listening to it, I realised I had been avoiding this kind of tempo.

That same month, almost without planning, I returned to Twin Peaks. Twice before I had tried and failed. I found it “too slow,” too resistant to my need for constant movement. But Perverts prepared me differently. It slowed me down enough to enter Lynch’s world, to sit with the fan turning on the ceiling, with the silences that refuse to end. Suddenly, the pace that once repelled me began to feel necessary, even generous.

This summer has become a bittersweet mix of the two—Cain’s sprawling hymns and Lynch’s haunted small town playing against each other in my daily rhythm. I move between them as though between two different registers of slowness, both urging me to linger, both teaching me that delay is not emptiness but another form of attention.

David Lynch’s Twin Peaks has always unsettled audiences with its slowness. The camera lingers too long. The silence between characters stretches until it becomes unbearable. A ceiling fan turns and we are forced to sit with it. Nothing moves quickly, and when something does, it is more horrifying because of the wait that preceded it. The show builds its world not by acceleration, but by asking us to stay in the awkward, the eerie, the unresolved.

This way of being—this insistence on delay—has leaked into other cultural forms. Ethel Cain’s Perverts carries traces of Twin Peaks in its bones. The Southern gothic imagery, the doomed love, the small-town decay: all of it breathes in a rhythm that is never rushed. Cain does not mimic Lynch, but she lingers with him. She sits beside his ghosts long enough to let them fade into new shapes. In this way, Perverts is not a pastiche, but a slow departure. It shows what happens when you hold on just long enough to let go.

Slowness here is not nostalgia. It is not about reanimating the past, nor about acceleration toward something shiny and new. It is about staying with the residue until it becomes fertile. It is about honouring what remains, without forcing it to perform usefulness. Lynch’s owls and Cain’s preachers share a time signature: not fast, not efficient, not “alive” in the sense demanded by productivity. They are suspended, waiting. They invite us to sit in that waiting.

To move slow is to resist being streamlined into the logic of platforms and their metrics. It is to refuse the demand to be instantly legible, constantly available, endlessly updated. It is to say: I will linger with what troubles me. I will wait with what refuses closure. Slowness lets us inhabit the haunted intervals of culture, where meaning is unfinished and still taking shape.

When I look at Twin Peaks through Cain’s Perverts, and Perverts through the spectre of Lynch, I see a lineage of delay. I see artists who work against the violence of speed by turning their attention to silence, to boredom, to residue. The lesson is not about reproducing a style, but about sustaining a temporality: dwelling in the discomfort of slowness until something unexpected emerges.

This is also a queer temporality. Queer life has always been about surviving the wait—waiting for recognition, waiting for safety, waiting for a future that is uncertain. But queerness also finds joy in that suspension. It finds ways to linger together, to share the insomnia of the night, to whisper across networks of care that stretch beyond borders. To move slowly is to create a space where this kind of intimacy can exist.

I think of slowness not as lethargy, but as an act of generosity. It is the decision to give time back to the work, back to the body, back to the ghosts that still want to be heard. To refuse the push forward is to make space for listening, for endurance, for connection.

And so, this epilogue is not an ending. It is a request to linger, to hold the moment a little longer, to stay in the unresolved. Like Lynch’s ceiling fan, like Cain’s hymns that stretch into dirges, slowness carries us to the threshold of something else. The dance continues, but gently, and we drift with it—not toward closure, but toward another beginning.