If we visit a physical event, we buy a ticket well in advance, dress up for the occasion, and maybe even meet up with a friend for something to eat. We cycle, drive, and travel to the event location. We can easily spend half an hour preparing for an event—an important transition moment in our day. But these kinds of pre-event rituals have yet to emerge for online events (and we’ve really missed them).

Resisting the digital blur

Pre-event rituals ensure that the audience makes a clear and distinct transition to your event. This is extremely important, not only to get their full attention, but also to give them the best experience. In his book Flow, the psychology of optimal experience, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi reveals what makes a human experience genuinely satisfying. And one key element of such flow-activity is having a well defined goal. Csikszentmihalyi gives the example of a surgeon, whose work has clearly defined tasks (removing a tumor or splinting a bone) compared to a psychiatrist, for example, who is often presented with problems that are not so clearly defined. Csikszentmihalyi points out the ceremonial steps of the surgeon: “Before an operation surgeons go through steps of preparation, purification, and dressing up in special garments—like athletes before a contest, or priests before a ceremony. These rituals have a practical purpose, but they also serve to separate celebrants from the concerns of everyday life, and focus their minds on the event to be enacted.”1

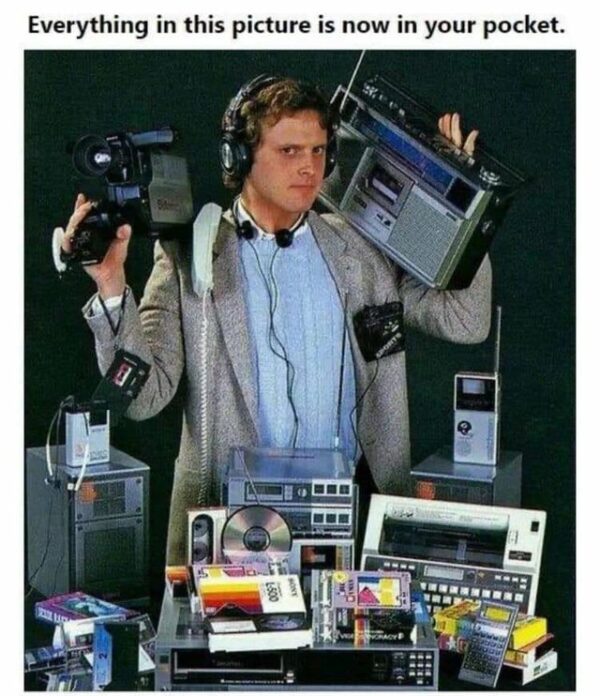

These meticulous rituals are almost the opposite of our online habits that emerged during the lockdown. During the day we worked from behind our laptops at our kitchen tables, and in the evenings we visited online theater performances on those same laptops, in those same kitchens. Our colleagues appeared in the same windows, within the same interfaces, as our friends. All the way back in 2000, Experimental Jetset created the Lost Formats Preservation Society—an archive of disappearing formats, from CDs to microcassetts to viewmasters. They write that “[t]here once was a time when every format contained its own specific data, while nowadays the CD-rom format is capable of containing all data, and even the CD-rom is slowly disappearing”. Twenty-two years later we’re in a moment where the distinction between different social, personal, and professional interactions is dissappearing, with every aspect of our lives mediated by screens. The formats, the spaces, that contextualised our interactions are gone.

Our digital activities blurred into one, with constant video conferencing causing a pandemic of Zoom fatigue. In their research on social connectedness and excessive screen time during COVID-19, Apurvakumar Pandya and Pragya Lodha laid out a series of recommendations for socio-emotional connectedness, including that “[h]ealthy and discrete boundaries between the personal and professional temporal spaces is helpful”. Last year, Professor Jeremy Bailenson, founding director of the Stanford Virtual Human Interaction Lab, examined the psychological consequences of spending hours per day on these platforms. He noted that one of the four causes of zoom fatigue is the higher cognitive load of video chats—the need to exaggerate gestures, always frame your face, and look like you are listening. Bailenson suggested giving ourselves an ‘audio only’ break during long stretches of meetings, to take some space from consuming visual gestures and cues. So if you’re organising an online event or meeting, how can you help your audience avoid these unhealthy digital habits?

Five tips to get you (and your audience) started:

1. Be aware that an event starts as soon as you announce that it’s taking place

“90% of what makes a gathering successful is put in place beforehand”, writes event facilitator Priya Parker in her inspirational book The Art of Gathering. 2 That’s a lot! It’s important to realise your event or meeting doesn’t start from the moment people get together, but from the moment you announce that the event is taking place. You can ask your audience to do a specific action to prepare. For example, when organising a tour through five different presentation platforms, we asked people to prepare a few technical things in advance, in order to get the best experience: like creating a Discord account and making sure they had the right browser installed.

2. It’s important for the audience to know what to expect

One of our former Hmm speakers was Club Quarantine, an online only queer party that took place every night during the pandemic. Club Quarantine was a great example that, even if you’re just opening another tab on your computer, you can still transform for a party. For the CQ parties, the audience would get dressed up and decorate their rooms and houses like a club, complete with disco balls and lights. To get people into a party mood you have to prepare them in the pregame. Like Parker writes: “It is hard to get a dance party started when people show up subdued and in the mood for quiet conversation.” 3

3. Hospitality is important, especially for online events!

When people attend a gathering in a physical space, they enter a building where someone is there to welcome them and tell them where to go. This physical guide is absent at online gatherings. Your guests just have to open a link and don’t know in what situation they’ll enter into. That’s why with The Hmm we always send detailed (but fun) instruction emails to visitors of our events. And when our gathering starts, we make sure someone from our team is present in the online space we’re meeting in. Welcoming both the audience and the speakers, in the same way that you would have someone take your ticket and greet you at a physical event. This might sound a bit obvious, but we have visited plenty of online events where this crucial piece of hospitality is forgotten.

4. Create a sense of community and togetherness

When we’re working mainly online, it’s hard to intervene in people’s physical environments. In an interview we did with media scientist Esther Hammelburg she said: “I think that the physical location of visitors might play a role during online events, only this is something we have yet to learn.” With the Hmm we’ve tried to get a sense of where people are by asking them to share photos of themselves watching The Hmm or asking them to let us know in the chat where they are watching from. But intervention into the physical environment can be taken even further. One thing we’ve seen organisations do is sending their audience packages with ingredients for making food, crafting supplies, or even a cocktail mix in advance. For example, for the Brexit Banquet—an Online Eat-A-Long with the Center for Genomic Gastronomy—audience members were given a list of ingredients to buy so that everyone could cook together.

5. Guide your audience through strategies to focus

With our last Hmm event, in December of 2021, we invited artist Annika Kappner to take our audience through a short guided meditation to transition them into our event environment. Annika guided the audience to close all the tabs on their computer or phone that were not related to the event, put on comfy clothes, and get their favourite drink or snack. Having the guided meditation prior to the event created a moment of space and transition before the event began. Some of our audience loved this moment of relaxation, while others loved it a little too much; saying that it made them too relaxed and unable to focus on the complex topics of our speakers. Overall, we learned that this moment of transition is a valuable way to create distinctions in online activities. Putting on comfy clothes to watch an event from home has a similar purpose as a surgeon putting on their scrubs before entering the operating room.

With The Hmm we’re experimenting with hybrid events and different formats this year. This text is part of our Hybrid events newsletter series where we share our learning lessons and experiments. If you haven’t already, you can sign up here to receive our newsletter in your inbox.

References

| ↥1 | Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Harper and Row, 2009, p. 165. |

| ↥2 | Parker, Priya. The Art of Gathering: How we Meet and Why if Matters, Penguin books Ltd, 2018, p. 149. |

| ↥3 | Parker, Priya. The Art of Gathering: How we Meet and Why if Matters, Penguin books Ltd, 2018, p. 152. |