The Chinese online celebrity Qiao Biluo attracts thousands of viewers with her beauty tutorials on the live-streaming platform Douyu. During a stream on 25 July 2019 her fans got the shock of their lives. For a split second, Qiao’s pink cheeks and smooth skin suddenly got removed from her face by a technical hiccup. The charming twenty-year-old streamer actually turned out to be a middle-aged woman with a filter on her face, with only a face filter separating these two identities.

You could say that China has an obsession with beautifying filters. Young people prefer to see themselves like how they look online—on selfies and live streaming platforms—where they almost always use filters to upgrade their appearance. Because facial recognition technology is integrated in many aspects of their daily life, Chinese people get confronted with how they look much more often than we do. In China you pay with your face, you enter school by showing your face to an iPad, and if you jaywalk, your face gets projected on a big billboard along the road. Research from the news platform Sina Technology showed that 60% of the people they surveyed feel ugly when their face is scanned when they make a payment. As a result, Alipay—the developer of the Smile-to-Pay systems—rolled out beautifying filters for all of its facial recognition payment systems in the summer of 2019. While China might be one step ahead of us by forcing beautifying filters (with Smile-to-Pay it’s not possible to turn off those filters) for public services, in the west augmented reality (AR) face masks are also extremely popular. We use them to make ourselves less vulnerable in our selfies and to hide our pimples and under-eye bags. AR face masks make our real faces less recognisable for our friends and family, but are we also becoming less recognisable for the platforms where we upload our images? Is the tool that is obscuring our faces also protecting us against facial recognition systems?

From dog filters to digital make-up

AR filters were part of Snapchat’s recipe for success. They put an end to our selfie shame and, along with the temporary character of the snaps, they made users share more content. You can roughly break the first Snapchat filters down into three categories: beautifying filters, filters with a fun-house-mirror effect, and filters with which you change yourself into another person, animal, or object. The app offered up to five different rabbit ears to put your head. Because of their illustrative and cartoon-like character, the filters let you only transform to a clear goal: a handsome person, a deer, or a rainbow vomiting clown. A lack of abstraction caused little room for our own imagination. Snapchat’s success triggered copycats. In 2017, two years after Snapchat’s introduction of AR filters, Facebook integrated filters on all their platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger). Around the same time, filters also became extremely popular in East Asian countries. It was not just the AR technology that was copied, but also how the filters looked—resulting in every platform having their own dog mask or flower tiara.

The uniformity of filters came to an end when Facebook -that owns Instagram- invited artists to design their Instagram filters. Illustrative cartoon figures got replaced by futuristic and shiny masks. Instead of dictating a beauty standard inspired by Kim Kardashian, the new filter designers were rebelling against the idea that everyone should aspire to look a certain way. 3D artist Ines Alpha for example uses her filters to discover the potential of digital make-up. Instagram’s filter diversity increased even further in August 2019, when the platform allowed everyone to design and upload their own filters. Spark AR, a studio tool from Facebook that allows users to create their own AR effects for Facebook and Instagram, is free to download.Thanks to the enormous amount of tutorials available on YouTube, everyone can get started.

But how do we pay?

Free is almost never really free. We use Facebook to see what our friends are up to, or keep our family updated on our lives, and we pay with our data. The social media company would never develop software and offer it for free if it wasn’t generating something of value for them. According to Andrew Bosworth, their vice-president of the Augmented and Virtual Reality division, integrating AR and VR on a consumer level is extremely challenging. Not only is the technology itself a barrier, so is its social acceptance. We are now so used to our computer mouse, keyboards, or touch screens that we find it difficult to navigate without these devices. Currently the face filter is one of the most widespread AR applications, and Spark AR studio is used by hundreds of millions of people. Facebook is using Spark AR as a way to better understand how they can improve AR technology for our near future. “We really believe this is the next frontier of computing”, said Bosworth during an interview with Harvard. “Instead of cell phones, people will one day have a constellation of augmented reality devices on their person. But the path from here to there isn’t all clear to us or to anybody else, so we have to invent it and that is exciting.”

So by giving their mask program away for free, Facebook gets many things in return. Besides gaining insights into how makers and users interact with the technology, which helps Facebook in further developing AR, it’s also an incredibly smart way to make us even more hooked. With Spark AR, the company has created a playground within which it is not Facebook employees, but other, unpaid, users, that develop tools that make Instagram and Facebook more attractive. After developing the software the company doesn’t have to spend any energy or money on it. They let artists and amateur makers discover its many potentials and create the products that ultimately benefits the platform. In addition, AR filters are a great way for Facebook to train their facial recognition systems. Through those innocent-looking dog masks we get captured by Facebook and get accustomed to the integration of this technology in our daily life. AI researcher Luke Stark underlines this in his essay “Facial recognition, emotion and race in animated social media“: “These interfaces are privacy “loss leaders,” drawing in smartphone users with a seemingly innocuous use case in order to cement the widespread use of a highly invasive form of surveillance, and enhance the capabilities of the technology itself.”

Chances are that your face is stored in Facebook’s enormous face database. Via their platforms, the company collects valuable information about the social lives of more than 500 million people. Facebook states that it is using facial recognition technology to suggest tags for photos. This is helpful, according to the company, because it prevents photos of you getting spread on the platform by friends or strangers who, knowingly or unknowingly, forget to tag you. What most users didn’t know is that all uploaded photos were automatically scanned by the recognition software. After much criticism on their privacy settings, the platform publicly announced in September 2019 that they were going to disable this function by default and only offer it as an option. According to digital rights organisation EDRi the opt-in only makes sense to new, not yet registered users, because the faces from people that were using Facebook before September 2019 are already part of their database. This data is really valuable to the company. They use facial recognition technology to better train their machine learning algorithms as a way to compete with other Big Tech companies. To illustrate this: Instagram’s image library alone is 10 times the size of Google’s image training set. Although Facebook says they don’t share our face data with third parties. But Facebook has not been the most transparent company. Fact is that they do make money from their algorithms, by using vast amounts of personal user data to sell targeted advertising or to predict user desires and ‘rent’ those desires out. That’s why EDRi (European Digital Rights organisation) is naturally sceptical of what Facebook does with our face data behind closed doors.

What information does Facebook collect when we put on an Instagram mask? “The Spark AR software allows filters to detect a face identify three expressions—smiling, kissing or surprised—and track a person’s hand”, writes tech journalist Dave Gershgorn in his article How Instagram’s Viral Face Filters Work. This is a limited set of tools if you compare it with what AI systems can do nowadays. An Instagram filter recognises a face as a face, looks where the face is, and draws a line around it to separate the face from the rest of the environment. In and of itself, the software doesn’t link the face to an individual person, which does happen with the photos that you post on your feed or in your Stories. When we post a selfie with a virtual mask, it may be more difficult for the facial recognition technology to identify us. Could we then use the filters to make us unrecognisable to the company’s face database?

According to Lotte Houwing, who is researching facial recognition for digital rights organisation Bits of Freedom, a face filter could possibly thwart facial recognition if the filter alters enough of the points on the face that are used to measure it. “But if you want to protect yourself against Facebook’s facial recognition tool on Instagram, you’d better use a filter from another platform, like Snapchat. Facebook knows exactly what happens to a photo when the filter is applied.” The company acknowledges this in their own regulations. When we use their services, they collect all information and data that we provide. We give them permission to access our camera, which means that our face is already being scanned before we put that dog mask on.

A good year to cover your face

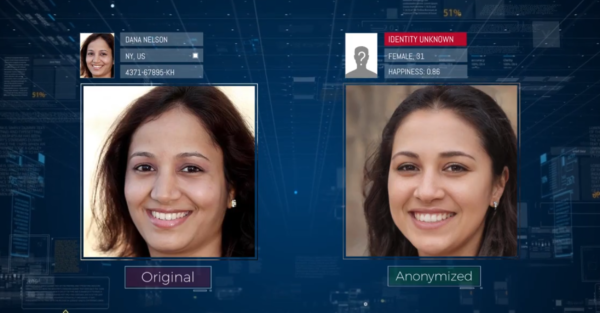

If you don’t want to give your face away, but still want to try Instagram’s amusing filters, the filter from the Israeli company D-ID might be the solution. Founders Gil Perry, Sella Blondheim and Eliran Kuta are concerned about the integration of facial recognition systems in public life and what governments will do with this data. That’s why they developed a tool that allows you to turn a photo of yourself into an AI-generated image of a person who doesn’t exist but looks exactly like you to the human eye. In this way, the facial recognition technology cannot link the photo of your face to you as an individual person and your other data points online. Not only can the tool protect the privacy of citizens, it can also be used by privacy-sensitive organisations who hold large repositories of photos from employees or patients and need to comply with privacy regulations. So far, this software is not yet available for personal use, but D-ID looks into the possibility to do so in the future. D-ID’s tool is just one of the many examples of technology solving the problems of facial recognition. There are several AI researchers working on algorithms that fool facial recognition technology, like PrivacyNet, AnonymousNet and Fawkes. Most of these algorithms are adding for us invisible pixels to a face that mislead the recognition software.

In June 2020, The Black Lives Matter protests has rushed developers and platforms to build tools that protect the faces of protestors. On June 3rd, the secure messaging app Signal stated that “2020 is a pretty good year to cover your face” as they announced a new blur feature in their image editor for iPhone and Android devices, to help protest the privacy of the people in the photos users share. In the same week, San Francisco-based software developer Noah Conk released an iOS shortcut that automatically blurs faces and wipes all meta-data relating to GPS location, time and the camera with which the photo was taken. To create this tool, Conk used Amazon’s facial recognition system Rekognition. Over the past years, government and law enforcement agencies have eagerly used Rekognition to identity suspects. Now the same software is also used to protect suspects.

Our ambivalent attitude towards facial recognition technology is interesting. On the one hand, we tend to be critical. We think it is scary that we are followed when we do our groceries or go to a football match. In the west, it probably will take a while to get used to the idea to pay with our faces. On the other hand, when a funny AR filter goes viral, the whole internet seems to easily give away their face and swap their gender or show which Disney character they are. Users embrace filters for fun and to make themselves feel less vulnerable. Under the pretext of this, they help the algorithms improve and get more used of the technology being integrated into our daily lives. This is not only a bad thing. As the tool of Noah Conk shows us, the technology can also solve the problem it created. But this is not the case when we put on a digital mask. To activate the AR mask on Instagram, we must show our face to the camera of our mobile device. While we might hide our face from our followers, we are not hiding it from Mark Zuckerberg. The company benefits from our filter addiction in multiply ways. It’s important to be aware of that while we scroll through their filter library.

The image featured with this article is made with the Instagram filter Isle of Palms by Eddyin3D.