The Bernie Sanders mitten meme, Lil Nas X’s satan shoes and Oprah’s interview with Harry and Meghan are among the most viral internet trends this year. All these trends have their origins in North American or European cultures—just like internet phenomena such as Pepe the Frog, Grumpy Cat, and Sponge Bob. Although the photo of the Shiba Inu dog, who later became Doge, was posted on the blog of a Japanese kindergarten teacher, the Tumblr Shiba Confessions turned the photo of the dog into a meme. Emoji also originated in Japan, but are now mainly managed by organisations and companies based in the U.S. This ensures that, in addition to Japanese culture, American culture is is overrepresented in the emoji collection. When things are written about internet culture, especially when written in English, it is often about trends, platforms or tools that are used and developed in North America or Europe. With The Hmm we do the same. For this article we decided to look more critically at our own filter bubble’, and investigate how the internet works in the so-called “rest of the world”. We asked a number of people from different places in the world, from Russia to Zimbabwe to China, to give us insights into how the internet looks from their perspectives. Before jumping to those results, I want to start by framing the asymmetries of internet use and internet access around the world.

Connection

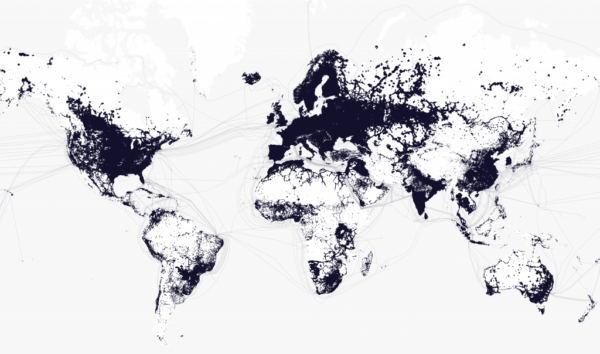

For a long time, “offline” and “online” were seen as two separate worlds. Now, there is so much overlap between these two worlds that we can hardly make this distinction. Superbowl performances are being discussed on the internet and dance schools started special lessons to teach TikTok dances. With increasing access to the internet through our iPhones, fitbits, and laptops, everyone is continuously present both physically and virtually. Internet culture is our culture. But a connection to the internet is not always so common. While 97% of the inhabitants in the Netherlands have an internet connection at home, by January 2021 only 59.5% of the world population had internet access. Especially in Asian and African countries the internet penetration percentage is low. In Eritrea and South Sudan only 7% and 8% of the residents, respectively, have an internet connection. In North Korea there’s no access to the global internet at all (unless you’re a high ranking official), but the country does have its own intranet. These disconnects have been made clearly visible via the interactive world map White Spots, made by information designer Richard Vijgen and documentary maker Bregtje van der Haak in 2016.

For technology companies, it’s economically interesting to focus on these partly disconnected countries, because there is a great opportunity for growth and new markets to capture. Since large percentages of the population in the United States and Europe are connected to the internet, people are already using certain tools and platforms and have developed certain online habits. In African and Asian countries these companies can win over new users. For example, the digital infrastructure in Africa is mainly organised by companies that are not from Africa. All elements needed to connect the continent so that the digital economy can grow, such as submarine cables, fiber-optic networks and data centres, are in the hands of the five largest telecom companies in Africa: Orange, Vodacom, Etisalat, Airtel and MTN. Except for MTN, none of these companies is fully African owned.

Facebook wants to connect the unconnected

Since 2014, Facebook has had the ambition to connect the whole world. That year, the American company launched internet.org, stated as ‘a global partnership between technology leaders, nonprofits, local communities, and experts who are working together to bring the internet to the two thirds of the world’s population that don’t yet have access’. In recent years, the project has changed its shape and gone by different names (Free Basics or 2Africa), but the impetus behind it, to connect people, has stayed the same and has not always been successful. Although Mark Zuckerberg likes to advertise it as a philanthropic project, he doesn’t realise—or he does, but prefers to hide it—that Facebook’s interference stands in the way of the development of local technology companies in these “disconnected” and often less economically powerful countries. The ‘help’ even comes unsolicited. In her article Algorithmic Colonization of Africa, Abeba Birhane writes: ‘Statements such as “creating knowledge about Africa’s population distribution”, “connecting the unconnected”, and “providing humanitarian aid” served as justification for Facebook’s project. For many Africans this echoes old colonial rhetoric; “We know what these people need, and we are coming to save them. They should be grateful.”’

“Zuckerberg is the guy who comes to your party and drinks your champagne, and kisses your girls, and doesn’t bring anything” according to Denis O’Brien, chairman of the international wireless provider Digital Group. As part of internet.org, the company wanted to make business deals with local telecom companies to offer customers a free app that had access to a few services like Wikipedia, health information, and Facebook. According to Zuckerberg, this was a great opportunity for operators, because they could get new customers. In fact, the telecom companies were not interested at all. “They were already concerned that people were communicating through services like WhatsApp and Facebook instead of the more lucrative text-messaging services they offered. They’d spent the money to lay down fiber and build an actual network, and people were now opting not to pay them for minutes”, writes Jessi Hempel in the Wired article ‘What Happened to internet.org, Facebook’s Grand Plan to Wire the World?‘. In addition, Facebook’s offer has far-reaching consequences for users. The company’s free app ensures that residents of these often less prosperous countries do not have access to the full internet, instead Facebook becomes their internet.

Facebook’s FreeBasics program was not accepted with open arms. In early 2016, India’s telecom regulator blocked Facebook’s Free Basics service because the project would jeopardise net neutrality. Yet this did not prevent Facebook from further investing in connecting the unconnected. Free Basics is available in 63 countries and Facebook has successfully delivered internet connectivity to people in those countries—people who otherwise might not have the resources to go online. And in May 2020, Facebook launched a new project: 2Africa, an international submarine telecommunications cable around the African continent that will interconnect 23 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

Accountability

Facebook has an enormous urge to connect, but is hardly concerned with the consequences of this universal connectivity and the fact that people from all over the world use their platforms. Julie Owono, executive director of Internet Without Borders, says in the podcast Your Undivided Attention that Western platforms like to offer their services in different countries, but do not have content moderators who speak all languages. On the African continent more than 1500 languages are spoken, while Facebook only has 20 major languages that they do fact checking for. Cambridge Analytica, Russian hackers and troll armies, who are known to exert political influence via social media platforms, can go specifically to countries where no content moderation takes place. Consequently, hate speech is a big problem in African countries. Not only on Facebook, but also on TikTok.

The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal during the 2016 US elections opened most people’s eyes to the influence of technology and social media platforms on the results of political elections. But residents of India or countries in Africa have been dealing with this since the early 2010s. The Myanmar genocide is a good example of how hate speech on Facebook can get out of hand. Still, Zuckerberg only had to confront the consequences of the power of Facebook in 2016 after the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Companies such as Facebook and Twitter operate around the world and cause problems around the world, but they are so powerful that if you want to hold them accountable for their actions you need a strong and solid government model. This is often lacking on the African continent.

Kenyan writer Nanjala Nyabola talks about this in the podcast The Horn: ‘We have multilevel challenges, especially in Africa because it’s coming at us from all directions. We’re getting American companies not responsive to Kenyan rights, Chinese companies building the surveillance architecture in Kenya and European countries getting involved in our elections, as a citizen I look around and think: “Where do I get protection”.’

With so little intervention by the platforms, the governments in some African countries regularly shut down the entire internet, especially during elections. It’s happening more and more. According to independent research organisation Access Now there were 25 documented internet shutdowns in 2019, twice as many as in 2017. This does not only happen in Africa. In 2020, most internet shutdowns happened in Southern Asia, especially in India. Myanmar has the longest-running internet shutdown. Residents there have not been able to go online since the beginning of 2019. Governments say they shut down the internet to protect the safety of citizens. “National security,” “public safety concerns” or “preventing the spread of misinformation and disinformation,” are often cited motivations, but actually it is a form of censorship. A 2019 research paper showed that out of the 22 countries that have disrupted access to the internet in Africa, 17 were authoritarian. “Increasingly, governments are using some of the problems created through an unfettered access to information and the lack of regulation and moderation” states Julie Owono in the podcast Your Undivided Attention: Facebook Goes ‘2Africa’. By taking control over the country’s communication channels, governments can take extreme actions without the whole population being aware of it because it cannot be spread via the internet.

Our research

Although the politics of the internet differ enormously—within the European Union we would not imagine the government shutting down the internet during election time, on the other hand, we also seem to have more power to hold American platforms accountable— our research shows that worldwide there is a lot of overlap in internet use. (Before discussing the results, it is good to know that the survey was conducted among a small number of respondents, whom we approached via our network).

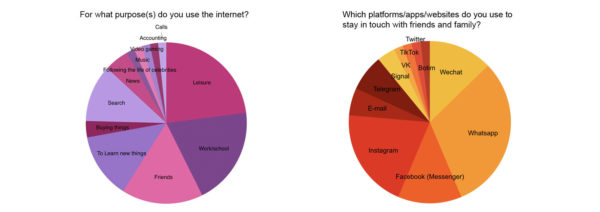

Our respondents from China, India, Russia, South Africa and Zimbabwe are online for similar reasons. “Leisure time”, “contact with friends” and “work” are the most popular answers. Also “learning new things” is often mentioned. Facebook is successful in spreading their services worldwide, with or without a free Free Basics app. In all countries their platforms (Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram) are used for contact with friends and acquaintances. In China WeChat is also popular and in Russia it’s Telegram but in both countries Facebook’s platforms are at least half as popular. Almost all respondents from Russia (80%) use Telegram for their news consumption. Getting news via a private chat app is a way to avoid social media’s personalised algorithms, or be informed about things that are not tolerated by the government. According to research from Antonis Kalogeropoulos the need for privacy and control of one’s audience is the most cited motivation for using mobile applications for news.

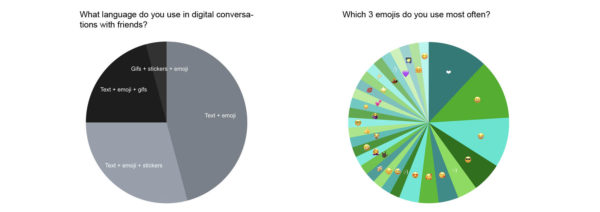

The question “Which platform is used to search online for what you’re looking for?” has the most similar answers. Although a number of Chinese respondents also use Baidu, Google is most frequently mentioned (87.5%) as the most used search engine. Interestingly, no one uses only text during digital conversations with friends: 46% send text and emoji and 28% send text, emoji and stickers. People’s favourite emoji vary a lot. Among the Chinese respondents 😂 and 😊 are most popular. When an emoji has to convey a genuine joy in China, it is important that the eyes are also smiling, as stated in this article. This 🙂 is seen as a smile out of courtesy.

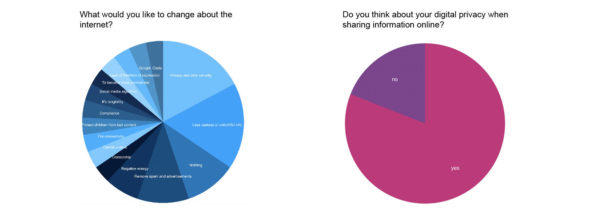

Communication and contact with friends or family is what people would miss most during an internet shutdown. One of the respondents in South Africa writes “I might welcome such a shutdown actually!”. Half of the respondents from India do not want to change anything about the internet. Most other respondents do. “Less useless or untruthful information”, “privacy and data security” and “spam and advertisements” are answers that occur several times. A respondent from South Africa would like to make the internet cheaper: “In South Africa data is very expensive and it is a huge huge issue limiting access for millions.” This is also something Julie Owono points to in the podcast mentioned above. In African countries internet connection is not often way more expensive than in Europe, the costs also differ a lot within the continent. This is also shown by the Worldwide mobile data pricing 2021 statistics on this website. There are three African countries in the top 5 of countries with expensive internet. Equatorial Guinea is most expensive with a cost of $49.67 for 1GB of internet data. In Sudan 1GB only costs $0,27, which is the cheapest internet connection worldwide. How is that possible? When Owono researched this she found out that the consortia that manage access to the infrastructure are very untransparent.

Almost everyone in our survey (82%) thinks about digital privacy when sharing things online. Someone from Russia wrote: “I check cookies, I use VPN, but I am aware that my google accounts already have enough on me, even though I turned off location and ads suggestions”. Although this is only a small survey and our respondents are, of course, not representative of all internet users, it is striking that the respondents from Zimbabwe do not think about their internet privacy.

How we deal with privacy or surveillance is determined by our cultural background and the systems that we have grown up with. In her book The Next Billion Users, about how people in the Global South are using the internet, anthropologist Payal Arora states that surveillance has a colonial heritage. “These communities, particularly in developing countries, have long been used by the state to test out new surveillance techniques. Hence, it should not be a surprise that the poor have come to expect and even live with these tools of control”, writes Arora. The internet users from the Brazilian favela, from Arora’s research, are very aware that they are constantly being monitored or that their passwords are being hacked. For them, being online is not something private, but something public. While most internet users dislike personal advertisements, which we also saw in our small research sample, Arora found out that Indian youth living in slums, for whom being online is expensive, thought these targeted ads conveniently saved them time and money. They don’t have to spend many hours—online or offline—looking for a good deal.

In the beginning of her book, Arora writes about her experience working on a development project where she helped to build computer kiosks with internet access in a small rural town in the South of India. The idea was that the connectivity would help the community to climb out of poverty. Arora writes that “We envisioned women seeking health information, farmers checking crop prices and children teaching themselves English via the kiosks.” Instead, the kiosks became gaming stations. Probably the same would have happened if these kiosks would be standing in more prosperous areas. When American or European companies bring their tools to the rest of the world, they often do the opposite of helping local communities. They hinder the development of local initiatives and the construction of a digital economy. And they even harm local communities, because they bring tools developed mainly by white men in the U.S. to a completely different context. And they don’t have any robust systems in place to protect people, against hate speech, hacking, or misinformation.

In reality, these companies don’t care so much about people, they just want them as users. Instead of helping local initiatives to build up a digital economy, they want to be the digital economy. “Because they (the Global South) constitute 86% of the world’s youth, they promise to be a lucrative market”, writes Arora. The fact that our research shows that there’s a lot of overlap in the tools internet users worldwide use, shows that American tech companies are on their way to win over these next billion users.