This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

For The Hmm’s Data Centre Tour in September 2023, we were joined by architect and editor Paul Cournet to explain the architecture of data centres and the cloud. Together with architect, educator, and researcher Negar Sanaan Bensi, he ran the studio Datapolis at TU Delft and edited a book that carries the same name, which was published in June 2023. During Paul’s talk, many follow-up questions were raised that still needed answering, so Sjef van Beers invited him and Negar back to answer them here.

Sjef van Beers: To start off, could you tell me what the Datapolis project is exactly?

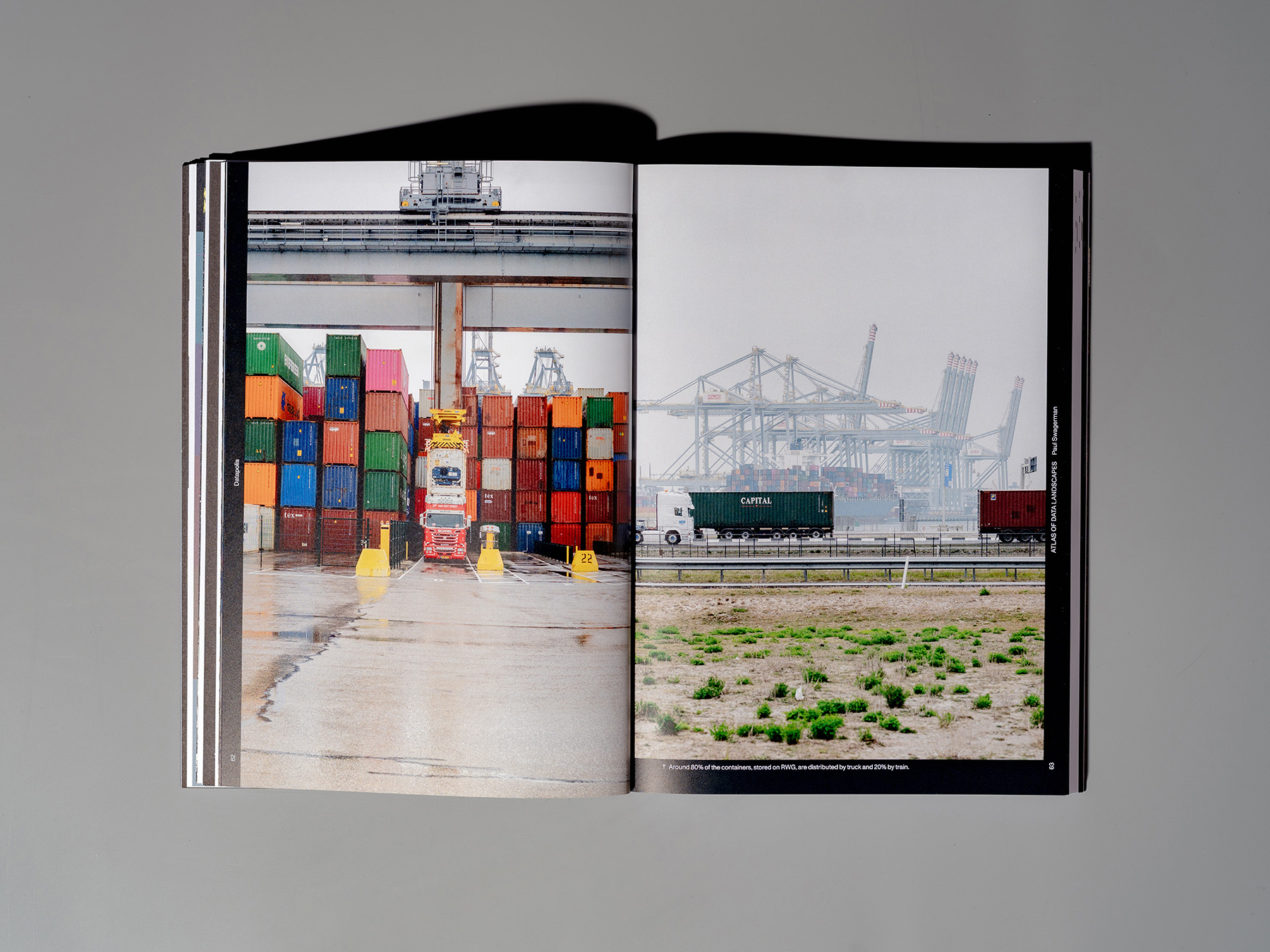

Negar Sanaan Bensi: Datapolis was a project that we started in 2019 with a simple question: what is “The Cloud”? Where is the physicality of data or data infrastructure? We started as a design and research studio course in the architecture faculty at TU Delft. It was a challenge, especially architecturally, of how you can actually approach these spaces, and why they should be interesting for architects. Because usually we are the last ones concerned with these infrastructural spaces. So we ran the studio for three years. and a lot of different topics and questions came up. So we figured that we could continue the research in the context of a book, inviting other researchers and authors to join us. And we added other sub-projects. We had an idea for a timeline of data infrastructure, for instance. We invited photographer Paul Swagerman, who was my colleague when I was working at ZUS, to photograph the data related landscapes in The Netherlands. The Netherlands is an interesting case study in that context. There are a lot of industries and territories that are heavily reliant on this infrastructure of data, as they are semi- or totally automated. And we wanted to have a second look at the students’ projects too, in the context of suggesting future visions. Not only to revisit this landscape, but to think along with the students about how we can contribute spatially and visually to the future of these spaces. The book tried to bring all these things together in two trajectories: one looks at the physicality or materiality of data, and the other one looks at the agency of data. We have a certain way of life right now that would have never been possible without data. And we are interested in this idea of Datapolis as “the city with data”, you know, at any level. So we look at and think about everything through data, basically. And that is how the visions were materialised. I think that’s a quick summary. Maybe you want to add something, Paul?

Paul Cournet: No, I think that was a very good intro.

SvB: And you are still continuing with the project now, right, after finishing the book?

PC: Yeah, we are hopefully launching a sort of second or third chapter of the project called Datapolis Plus, in which we’d like to explore the project more in the format of exhibitions and symposiums. The idea will be to take what we learned from the book, and engage with a larger audience, with different contributors. We realised that while the project started very small within TU Delft, over the years, interest in it grew. And we connected with more and more people–architects, but also engineers, people working in tech, people working in culture, or any field really– who all had a different angle on that topic, that question of “what is The Cloud?” So we began from a very architectural perspective, and then started looking at questions of physical footprints, questions of health, questions of waste, questions of automation, the space given to our bodies. In this way we ended up with a much more multidisciplinary and holistic approach to the question of data.

SvB: Paul, you joined us for the Data Centre Tour. How was that for you? And had you visited that place before, the data centres in the Wieringermeerpolder?

PC: Yes, we have actually tried to get in previously. We contacted Microsoft and Google when we started this photography project with Paul Swagerman. But it became very clear that we would not be able to get in. The only way to enter those spaces was through the photos that they communicate online on their own channels. We wanted to get into the data centre to really understand: how is it made? How is the experience inside? So, we ended up contacting other data centres in The Netherlands. There are, I think, between 100 to 200 data centres in The Netherlands today. We approached the more independent ones, who actually were very welcoming and eager to show us the spaces and to have conversations with us. We visited, for instance, the AMS-IX in Amsterdam, the internet exchange point. And we went to one in Rotterdam, in Smartdc, which is a beautiful modernist heritage building in the Van Nelle Fabriek. We also went to the south of the Netherlands, to this Cold War bunker turned to data centre. Historically, it was a place for The Pirate Bay, but now a new company called Holland Datacenters rents it. They were all really different in terms of space and experience, and in management of energy and storytelling. It was very interesting.

SvB: When we were walking along the data centre during the tour, we had a Telegram group running a voice chat so people could clearly hear Paul and then Lukas Engelhardt, another speaker, as we were walking with quite a big group. Some people sent questions in the chat that we couldn’t get to during the walk. So I wanted to bring them up again here. To start off, someone asked: do you know who owns the ground the data centres are built on? Who else makes money off of this?

PC: Yeah, that’s a good question. Do you know, Negar?

NSB: I think they all have different stories. I’m not sure, but I think specifically this Microsoft one you visited was a struggle between the farmers and the municipality. I don’t know exactly how much ground was owned by each party. But every data centre has a different story. Some of them are privately owned. Some of them are under cultural heritage, for example the one in the Van Nelle that Paul mentioned. But these huge ones, like the Google and Microsoft ones, usually have deals with the municipalities they’re in.

SvB: Yeah, I think this was also mentioned by Lars Ruiter, who is a councillor in the municipality of Hollands Kroon, during his talk on the tour.

PC: Yes, I remember he mentioned that it is this whole play on tax breaks and trying to welcome these companies as much as possible. And in the end the ones who benefit are the owners of those lands, the farmers, and the cities that receive some tax payments. It definitely doesn’t benefit the local community. But I don’t know the specifics.

NSB: What they usually do–I think we also have a paper on this in our book, but it’s in the context of the US, not The Netherlands—is they usually make very good deals mainly regarding energy and taxes, often with the promise of hiring labour, which they don’t actually need.

PC: Can you tell us which paper it is, Negar?

NSB: It’s the paper by Ali Fard. In it, he tries to unpack the different layers involved in the formation of these data centres, from the economy of it, to the infrastructure, to legal things and environmental impact, etc. It’s called “Machines in Landscape: Territorial Instruments”. He addresses these layers and all the controversies that they bring with them, because these data centres come here with certain promises, and they hardly keep them.

SvB: Yeah, I think that was also the case for the data centre we visited. Another question from the chat was if it’s true that there were no architects involved in the construction of that data centre?

NSB: There are hardly ever any architects involved.

PC: Yeah, they have an internal team that designs those infrastructures. I think it’s firstly because they want to keep it very secretive, and secondly to run the machine in the most efficient way. Usually they are engineers, because—and this is what’s interesting, I think—the way they think about it is from the inside out. They start from the rack, from the unit of data storage, and then those get assembled into a column, and around that you need a cooling system, and that defines the location of the corner and the height of the ceiling, and so on. It’s like an onion, starting from the core and building different layers of technical solutions to given problems. All that ends up as a massive, hyper-optimised box. What you see on the outside is really a consequence of the way it’s been thought of from the inside out. It looks very dry, sort of machine-like, purely functional. There’s no intention at all to give a kind of external meaning, or some kind of architectural feature that could be a symbol for the community or the surrounding landscape. The only thing they did was paint some parts green, to make it blend in with the landscape. But yeah, clearly it’s just one of the, what we call, “boring boxes”. It’s like the architecture of a mall, you know, just a big box in a landscape with huge infrastructure noodles around them to bring the flows of product in and out. And it has a huge footprint. It was shocking, to me, the footprint of these machines in the landscape. It’s just gigantic.

NSB: Yes, and this is nothing new, right? I mean, throughout the 20th century we’ve witnessed the expansion and expulsion of our infrastructure to the outside of cities. Things like water filtration, sewage, etc. are migrating from inside the city to the outskirts. And they become huge machines. And at least with the architecture of shopping malls or airports, they can have interiors that become special or architecturally interesting. But for these machines, the interior too gets the logic of the technical, of solving the issue. I think architecturally they hardly have anything to offer. That was also an investigation for us. I think it is interesting to see how they can become more than just storage or transition of data. Most of these centres don’t involve architects, but they also don’t involve people like ecologists, for example, they don’t involve the environment. They don’t involve anyone else than just technical problem solvers. You know, last week we were invited to this green data centre conference, which was a huge event in the Netherlands. And they were very kind to invite us, but when you see the executives of these data centres… If you really want to address the problem of making a green data centre, you have to open it up to other kinds of specialists, communities, politicians, architects. I think they might be tired of the politics that are constantly putting pressure on them, and see that as a bad thing. I get that, but the approach should go beyond this “negative nagging” and this closeness of the field itself.

PC: And these are mono-functional buildings. It’s purely architecture for machines. So humans are only a very tiny portion of the equation.

SvB: That maybe connects to another question someone had: why are there so many docks for trucks at the data centre?

NSB: I think they have a lot of logistics. I don’t know how many docks there were or what it means to say “many”, but they are logistical buildings. They need maintenance.

PC: If you think of the pace of architecture—even though the data centres are built very quickly—it will take probably five to ten years to build one. But technology is replaced every six months. There’s this constant need for improvements on the machine: to optimise it, reduce the cost… Because, really, a data centre is all about optimisation: automated optimisation of cost, of flow of information, of space. So they build a box, whose parts, like a computer, can be replaced very quickly.

NSB: Yeah, and I also think you can hardly ever consider it a finished entity, such structures. They start with a very simple model, and then over time, if it makes sense economically, they start to expand it. For that, and for maintenance, they need logistics.

SvB: Alright. Paul, you mentioned in your talk–and I’m paraphrasing here–the decentralised setup of internet infrastructure, where, if one data centre were to go offline, its data could be migrated to another one very quickly. On the other hand, the internet can be defined as centralised, since it is being run by an increasingly small number of big tech companies. There was someone in the chat who asked: what about the internet cables, DNS, internet exchange points? Are they also privatised? Who owns them? Do you expect a future where these connections are also owned by a few monopolies? And would that prevent us from self-hosting and bypassing big corporations?

PC: You know, the internet was a dream. It was built with the idea that it would be very horizontal. It would open up new opportunities for humanity. I think it was a very humanistic project in the beginning. And now half a century later, it has become this global infrastructure that, indeed, allows us to communicate regardless of political borders or regardless of time zones, in a very, very efficient way at the speed of light. But due to its success, it also became an infrastructure for corporations to own. The result of that today is, while the infrastructure was originally built to be shared and fully accessible, now there are a few companies that are so powerful and have so much money that they’ve decided to build parts of this infrastructure by themselves. Essentially, you have two types of data centres, right? You have the hyperscale data centres that are owned by a single company, and the colocation data centres that are shared between different owners. And now, these huge companies are expanding their own parts of the infrastructure. They are stretching cables between the data centres they own. Which means some of these undersea cables, that we’ve all heard about that connect different continents, are now privately owned, by Facebook, Microsoft, Google. Step by step, they are creating a privatised internet infrastructure. And that means it will be much harder to regulate, and to know where information is stored, or where it is circulated, because there will be less transparency and authority over those infrastructures. This is already happening. And when we see the promises that these companies make regarding sustainability, and the contrasting opacity of their strategies, it is very easy to predict that it will be the same regarding questions of ownership of information and the overall durability of the infrastructure. So while today we still have global knowledge of the internet infrastructure, I think we will enter a new era where it will become much more difficult to understand how it works. I think the only way to have a positive impact here is to be strict on regulation. The same thing that’s happening now regarding energy. We realised, for example, that Microsoft and Google claim they are carbon neutral, but they don’t communicate their numbers. This means they can say anything, as long as it is not checked. And if I understood everything well during our visit, from next year on these data centre companies need to communicate their numbers. Hopefully then we will understand that the data centre is far from being green, the way it’s built today. I hope that that kind of regulation will also be applied to the infrastructure. That has to be, I think, the next step.

NSB: Yes, I was just trying to find a paper I want to refer to. It was a paper written by Peter Pomerantsev who is a Soviet-born British journalist, author and TV producer. His father was a famous writer, and when he was imprisoned by the Soviets, he had this dream about a world where he could write and everybody could read it. This massive accessibility. And the paper started from there and said, you know, now we have it! But now it is a problem that everybody has access to it, and everybody has an opinion about it, which is the other side to this massive accessibility. The consequences of that have gotten out of hand. And this is also the side we could have never imagined, when we were saying everyone is going to have access–though that is not entirely true actually, not everyone has equal access. And the internet is full of manipulation, right? Think of Bruno Latour, who says that facts are not clear and nobody can say what a fact really is. Even the concept of climate change is affected by this. So how can we deal with a society where even “the fact” becomes unclear? The internet has a lot of consequences, on the social level, the ethical level, the environmental level… And it’s also not fair to just condemn these companies, because they are providing what society needs. It’s a problem on a scale that we’ve never seen before. It’s the same as with climate change: how can you bring it to the individual, beyond the blame and the guilt, to make it collectively productive? I totally agree with Paul that things have to be regulated. The same way that now suddenly there is the need for oceans and space to be regulated properly. Even those things, that we have already had access to for 30 years, are not properly regulated. So I think this is definitely a next step. Ownership of data, for example, is still totally unclear. We had a student who started to keep track of what happens to a Facebook account after one dies. Then it becomes really clear how ambiguous the issue of the ownership of data is. The complexity of the internet, its infrastructure and its issues, was also something we delved into, to see all sides of it. We call it the many-headed demon, because it has good parts and bad parts all together.

SvB: I think that also links to the last question I wanted to ask: do you think it would be desirable for public authorities to requisition elements of computational infrastructure and treat it as public utility? And if so, how could that happen?

NSB: Well, I think that is a very complex question. There are different systems of governance for the internet everywhere. For example, in countries like Iran and Russia, they have totally centralised governmental systems. In Europe it is more based on corporations of private or semi-public bodies. And in the US it is mainly company based. And it’s a little more complicated than just saying they should become public. To have this conversation, all these systems have to be unpacked and discussed properly. I don’t think we have the expertise, at this moment, to do that. Or at least I don’t, maybe Paul can say something about it. But I think there probably should be a more complex system than just public or private. I think that the system of co-operations is interesting, but it needs to be better and more clearly regulated, and become more transparent to the public. Paul, what do you think?

PC: Oh, yeah, I completely agree. And to add to that, when we started the studio, besides doing research, we also asked the students to come up with visions. So the last chapter of the Datapolis book is called “Visions”, where we asked students to transform all of these complex issues into future scenarios. For me, when I really try to think of the future of data centres, I assume that the energy part will be solved somehow. It will take a few decades, probably, but somehow, hopefully, there will be some technical solution. They will put a data centre under water, or do something we don’t know yet, but something will happen. But that will not change the nature of the infrastructure. It will still be privatised. We will still have to come back to these issues of regulation and so on. If you look at collective spaces for storing information that are meaningful in our society today, you immediately think of public libraries. They are the best nodes within cityscapes in terms of accumulation of information and communication of knowledge. So you want the data centre of tomorrow to be the future public library. You want it to become a piece of the urban landscape that people can really cherish, value, and attach meaning to. Amazon and Microsoft and these other big companies are already opening more public buildings. I was recently in Seattle where Amazon built this sphere, a sort of Buckminster Fuller inspired centre. It is a space for exhibition and work. It’s a great heart for the city. Could the data centre of tomorrow be the public library? We have also discussed the question of encoding data in plants, like DNA. Is the data centre of tomorrow a garden where we will be able to grow peppers and apples and flowers? Is it a public swimming pool, because the water will be warmed by the systems? I think those are the actually interesting possible futures for data centres, to make them public in a way that communities can really cherish their existence.