Ah, to be young and have your music. To have been sixteen in 1962 and to upset your parents with The Beatles’ ‘Love me do’. It was so fresh and bold, so current and cool. I always considered myself lucky to have been the perfect age for Nirvana’s Nevermind. I remember vividly —or perhaps I falsely remember vividly—hearing the first chords at age 14 and knowing instantly that this was raw and authentic, something that’d define my generation. As I dove deeper into the punk rock of the era, I got to experience the classic generational conflict. Sonic Youth wasn’t music, my dad authoritatively stated, it was noise. He’d forgotten that his parents said the same thing about the Rolling Stones.

Ever since it came into being after WWII, youth culture has been associated with originality and authenticity, which together spell ‘cool’. But pop music hasn’t been the exclusive domain of the young for a while now. The boundaries between youth/subcultures and mainstream culture have been blurred, and young people have had to find new media to express their identities with. In this essay, I’ll argue that the popularity of the video sharing app TikTok amongst teens suggests that there’s more going on than a mere change in fashionable media and apps. TikTok’s success indicates a shift in the very definition of cool, which in turn heralds a transfer of global power from the US to China.

Hide and seek

Pop music has been colonized by the old, who were once the young. Keeping up with current music became a way for adults to feel hip. So dads take their daughters to festivals, festivals that for decades now have been programmed by old rockers who want to keep up with their fellow kids. Several Dutch festivals even offer babysitting services, so parents can rock on with their offspring nearby.

Luckily, youth culture is resilient and flexible. Teens will always create their own customs, find their own spaces where parents feel lost because they just don’t understand. The internet is the perfect place for that. Online, we’ve been witnessing an ongoing game of hide and seek. Adolescents flock to a platform, and when adults discover it, they move out. Consider the current fate of Facebook: contemporary teens have no interest in it, but they’re now realizing they’ve had a presence there ever since they were born. To them, it’s deeply and deadly a site that screams old age.

No parents allowed

Five years ago, the fashion was vlogging. Adolescents en masse tuned in to YouTube, leaving their parents dumbfounded. Why on earth did young people in their bedrooms enjoy watching lengthy videos of other young people in their bedrooms? As mainstream media reported on the phenomenon, vlogging became less incomprehensible and thus less impregnable. As a result, although vlogs and vloggers are still immensely popular, their appeal is fading.

Now, it’s TikTok, the Chinese owned platform that combines music with memes. Users create videos of 15 seconds max, and add music to them. As elsewhere online, challenges are extremely popular, as are other forms of mimicking (the key ingredient of memes). Accordingly, lip-syncing and dancing make for great viral hits on the app.

Navigating this mishmash world of music and memes requires a ‘youth cultural capital’ that is unattainable for most grown-ups. Furthermore, a new meaning of cool emanates from the platform, rendering it even less susceptible to adult immigration.

Class

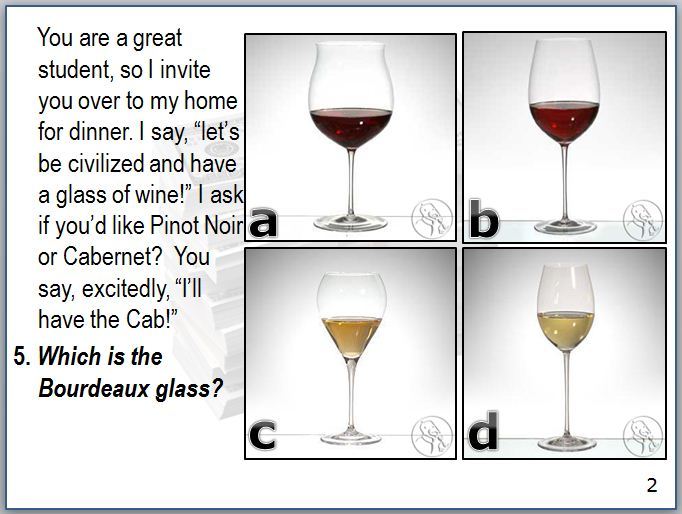

Cultural capital is a concept from the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. It can be understood as being in the know: knowing which products, which styles, which tastes are highly valued in a particular culture. Having the right cultural capital means you can distinguish yourself from others. It’s how class boundaries are drawn and upheld. Think of it as knowing which wine to order during a business dinner, or being able to talk about French sociology.

Thinking on a smaller scale than Bourdieu originally intended, each social setting or scene has its own forms of required cultural capital. To be able to ‘join’ the metal music scene, for instance, you need to know underground metal bands and ‘prove’ that you have what it takes, meaning: the right taste. This, we’d call subcultural capital. Likewise, ‘pop-cultural’ capital refers to your aptitude in pop culture.

The death of pop-cultural capital

In order to get the jokes on The Simpsons and South Park, one needs to have seen the films and shows they’re spoofing. However, search engines have killed pop-cultural capital: we can now look up all these things. Every single bit of popular culture is immediately disentangled on YouTube, and all its hidden and not-so hidden meanings exposed. Hence, pop-cultural capital is easily learned and thus faked. If you don’t know your meme, there’s a website for it.

This means that pop-cultural capital, to an extent, has lost its capacity to function as a social marker. Everyone can be in the know. With pop culture being global and round the clock, speed doesn’t help here either. There was a time when you could be the first one in your school to adopt a punk hairstyle, because you managed to get your hands on a copy of an overseas magazine detailing these latest trends. You could be original, or at least appear original. Those days are long gone.

Ambitious China

Enter TikTok. The platform is owned by the Chinese tech company ByteDance, that developed TikTok for markets outside China. On the internal market, the app is called Douyin. Having two names and two servers allows ByteDance to circumvent Chinese censorship laws. Douyin dominates the local market together with Kuaishou (known as Kwai outside of China), which is also a video sharing app but aimed at rural areas. ByteDance seeks to conquer the world, an ambition it shares with its native country.

For a long time, China has been seen as trying to catch up with the West. We think China wants to be like us, and is making up for its lagging position. It’s typical Orientalist thinking. It also reflects how provincial we’ve become. Our eyes are aimed at ourselves, we are obsessed with Brexit and Trump, and have little clue of what’s going on in Asia. The poor English language documentation on Douyin and Kuaishou testifies to that: Kuaishou’s Wikipedia entry is a mere 200 words long; Douyin doesn’t even have its own entry and is only discussed briefly under TikTok.

Copycat culture

Imitating the West is not what contemporary China’s about. The Chinese are nevertheless masters of copying. Whether it be the exact and careful copies of the impressionist painters sold outside the Van Gogh Museum, or the iPad rip-offs on sale in the endless shops of Shenzhen, China has perfected duplication.

Talking about this copycat culture, professor in Globalisation Studies Jeroen de Kloet emphasizes that China holds a different paradigm on creativity. The Chinese are not concerned with originality and uniqueness in ways that Western people are, they are developing their own understandings. China values the artisanal, and acknowledges creativity in stealing, reshaping and appropriating. Innovation then lies with small adjustments and rearrangements. Renewal, De Kloet argues, is doing the same thing differently.

Chinese innovation

This culture is deeply embedded in TikTok. The app doesn’t reward the first, it rewards the best. Copycatting is at the heart of TikTok. It’s taking a meme and re-enacting it, reworking it, remixing it. ‘Derivative’ is a word used by people in the West to show off their cultural capital in critiquing art. On TikTok, derivative means tribute. TikTok attests to the notion that there are qualitative differences in imitation. This is, of course, not to say that meme culture is Chinese in origin, it’s not. But TikTok is, and the platform mirrors China’s dissimilar approach to innovation.

Because make no mistake: China is definitely big on innovation, most notably in the domain of artificial intelligence. The little academic research that exists on TikTok focuses mostly on its recommendation algorithm. Like other social networks, TikTok’s algorithm decides what users see in their feed. However, TikTok does not facilitate existing networks of friends, but centrally directs its users to finding new people and new memes. The former echoes westerners’ provincial preoccupation with ourselves, the latter expresses a desire for expansion.

The new cool

It’s unlikely that TikTok will remain the pastime drug of choice for teenagers. Their hiding spot has been found out, and I regularly encounter TikTok videos on stale platforms like Twitter. However, TikTok content out of context does no justice to the culture created and celebrated on the app. It’s a misrepresentation of this youth culture, which is—paradoxically—one of the most gratifying things for a youth and media researcher like myself.

It shows that young people have once again found expressions of who they are in ways that grown-ups just don’t understand. When those adults realize that these manifestations of youth culture are a sign of global power shifting from the US to China, I’m sure they’ll be concerned about different things than stranger danger and privacy breaches. In a world where everything’s been done before, China knows that authenticity is no longer meaningful. TikTok teaches us that the new cool differs not merely from the old in terms of substance. The new cool is of an entirely other nature.

✨This is the sixth in a series of seven commissioned essays for 2019. With these original essays, our aim is to publish work that engages with digital visual culture, both in its niche manifestations and within the technological, political, and mainstream reality of the internet.