When Trump responded to the unrest during Black Lives Matter protests in Minneapolis in May 2020 with a racist reference, Facebook decided to not delete his post. In a statement, Mark Zuckerberg explained that, even though he personally did not support Trump’s post, he took the decision as the leader of an institution committed to free expression. Facebook employees disagreed so much that they went on a virtual walkout.

Facebook, whose famously strict nudity rules led them to delete 75 million posts in the first half of 2020, says they want to be a neutral platform that resists censoring its users’ speech. At the same time, they say that they want to “bring people together” and protect “their communities’” safety, privacy, dignity and authenticity. Why would Facebook deliberately decide that a politician like Trump can post things that violate their rules (“community standards”) and even jeopardise human rights? To better understand the motives that underlie the company’s choices for their content moderation, I had a conversation with independent internet policy consultant Joe McNamee. Content moderation has been one of his research topics over the past few years and he is currently part of the Council of Europe’s Expert Committee on Freedom of Expression and Digital Technologies, that is working on this topic.

Facebook’s real interest

Trump’s post is just one of the many examples in Facebook’s history where the company’s choice to delete or leave a post up has been highly criticised. There is even a Wikipedia page listing many of the notable issues Facebook has run into since 2011. The spread of misinformation is a well-known problem on its platforms. These problems don’t just stay online—they seep into the real world with often disastrous consequences. For example, in 2016 and 2017, the army in Myanmar used Facebook to provoke a genocide against the mostly Muslim Rohingya minority. During the 2016 US elections, the Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed how Facebook can manipulate people’s voting behaviour and, by doing that, harm our democracy. During his testimony to the U.S. Congress, Mark Zuckerberg not only apologised, but also promised improvement—a recurring pattern after the company makes a decision that attracts public criticism. What improvements have there been over the past few years? The New Yorker article “Why Facebook can’t fix itself” gives an interesting glimpse behind the scenes and shows which choices are being made internally. After reading it, I was amazed at Facebook’s seeming unprofessionalism. For example, their internal guidelines on content moderation, called “Implementation Standards”, is an ever-changing document that only content moderators and a limited number of Facebook employees are allowed to read. Users cannot gain insight into it.

According to Joe, instead of being a sign of unprofessionalism, this is part of Facebook’s strategy. To better understand Facebook’s choices, we need to realise that we are not their customers. The company would like us, their users, to believe that we are their main interest and that they are optimising their fantastic product to serve us well. In fact, we are not using the product, we are the product. The companies to which they sell ads or data services are Facebook’s real customers. Joe: “If you imagine Facebook as a fast food restaurant, its users are the French fries, not the diners. Facebook is a business that consists of data generation, collection, and exploitation—for commercial and political influence. It collects data generated within its own network. It also collects data outside its network—by harvesting personal information from other sites and services, such as from “like” buttons, from tracking cookies and hidden tracking technologies called “clear pixels”, invisibly tracking individuals who may not even ever have used Facebook. Its data collection also goes beyond what the data it collects in these ways. For example, it has been shown to generate data by experimenting on its users. So, its mission is to collect, analyze and generate data.”

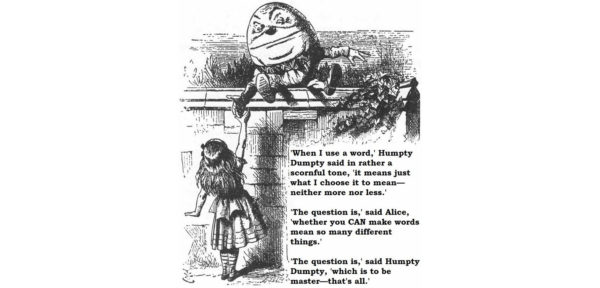

Their so-called mission to “bring people together” could be seen as an advertising slogan to convince us, their French fries, to come voluntarily to their fast food restaurant to be consumed by their actual, paying clients. The fact that their rules about content moderation are not fixed or understandable is a way to continue this activity unimpeded. Joe: “They are continually broadening their wording , so that they have as much flexibility as possible and the ability, politically, to be able to point regulators to rules that claim to address specific problems. ‘Look, we have rules on hate speech. Look we have rules on nudity. We prohibit [name of unwelcome activity] on our service. This shows we take [insert problem] seriously’. Or it just updates the words in its rules to give them new meanings. For example, after criticism of its psychological experiments on users to establish if it could change their mood, it said ‘when someone signs up for Facebook, we’ve always asked permission to use their information to provide and enhance the services we offer. To suggest we conducted any corporate research without permission is complete fiction.’ It was, apparently, obvious that ‘improve our services’ meant ‘mess with your brain’.”

Empty progress

The New Yorker article mentioned earlier states that “The company’s incentive is to keep people on the platform—including strongmen and their most avid followers, whose incendiary rhetoric tends to generate a disproportionate amount of engagement.” This is, of course, part of the economic logic of surveillance capitalism—profiting from clicks, engagement, and the ad revenue generated from that. Facebook doesn’t have and, from a business perspective, doesn’t need, a clear strategy for their content moderation. There is minimal leadership and no sign of a moral compass. It is as if trying to push the boundaries of how far they can go in allowing extreme content, without damaging the reputation of the company to such an extent that a significant amount of users would leave the platform. In the article, former Facebook data scientist Sophie Zhang says: “It’s an open secret that Facebook’s short-term decisions are largely motivated by PR and the potential for negative attention”.

Every time Facebook gets bad press, they state that they are committed to making progress. In a statement, Facebook spokesperson Drew Pusateri wrote that a recent European Commission Report found that Facebook assessed 97% of hate speech reports in less than 24 hours. Joe tells me this is a statistic from Facebook itself, which was ‘laundered’ through the European Commission, so that it looks like it is a positive, independent evaluation. Furthermore, this statistic ultimately tells us nothing. Joe: “What does that 97% mean? Were the reports processed correctly or not? Was the content that was subsequently removed illegal or not? If it was illegal, was anyone prosecuted? Was the content that was removed really in breach of Facebook’s terms of service or not? What is the real-world effect on hate speech? Are people dissuaded from hate speech because content is being removed more quickly or are they encouraged to post it, knowing that the only punishment is that the content will be removed after a few hours or days? Facebook often publishes press releases saying that x million examples of y have been removed but they produce no useful data to measure whether there has been “progress”. Neither they nor anybody else knows what progress is, nor what failure is defined as. We don’t know, because nobody appears to have an interest in finding out. Facebook certainly has shown little interest in transparency.”

The past few years have shown that if we expect Facebook to self-regulate their own platforms, there will be little or no change. They only start tackling misinformation about COVID-19 or deleting posts that deny the Holocaust after enough pressure from the media, researchers, or their users. This leaves us with the impression that they only take action because they want to ensure that their users, their French fries, keep on opening their Facebook pages and giving away their data. So far, this strategy seems to be successful. Despite the fact that the Cambridge Analytica scandal opened many eyes to the reality that the company is causing serious damage to our democracy—the scandal was even highlighted in a popular Netflix documentary— the vast majority of users still did not delete their Facebook accounts. Ultimately, if a significant minority did delete their accounts, Facebook would still be tracking them through Instagram, through Whatsapp, through the surveillance it operates through third party sites, or through Oculus VR. Facebook itself is designed like a slot machine—they know how to keep us there, interacting, for longer and longer. Another important reason that we keep on using them is that we, as users or French fries, fail to understand the workings and the effect of Facebook’s business model.

The fact that Facebook doesn’t structurally address the issues surrounding hate speech, misinformation, and privacy on their platforms makes perfect sense when you look at their business model, says Joe: “Facebook is a data company. Controversial content generates more engagement, and therefore data, from users. Facebook services are designed to generate more engagement from users. It is a listed company on the stock exchange and acts in a way that is compatible with the logical interests of such a company. A question like ‘Why doesn’t Facebook take structural actions to improve their content moderation on their platforms?’ should thus be rephrased as ‘Why does a service that is designed to increase engagement fail to take measures to discourage certain types of engagement?’”

Time for a change

For Facebook, it’s all about the clicks. On a platform like Wikipedia—that isn’t trying to optimise for engagement—misinformation and hate speech are much less of a problem. Should Facebook then change their lucrative business model in order to offer its members a safe and friendly platform?

In Joe’s opinion, some political leadership could save us, and save Facebook from itself. “It’s difficult, but not impossible, for Facebook to stick to a less aggressive version of its business model while maintaining adequate content moderation. To achieve improvements, there need to be incentives that currently do not exist. The problem itself (predictability and fairness of content moderation, transparency about what the content moderation is trying to achieve, clarity of terms of service, or community guidelines) and its roots (excessive exploitation of personal data, and lack of effective competition) need to be effectively addressed. For content moderation, without clear targets, incentives, and transparency, we are basically hoping for a miracle. There need to be clear rules on things like how predictable the implementation of Facebook’s rules is, how much data Facebook needs to make available to governments and researchers on content that is removed, not removed, amplified, de-amplified, information that is given to people who complain about content, information that is given to people whose content is subject to complaints or removed, etc. Separately, strict rules need to be enforced with regard to their exploitation of personal data. Proper implementation of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation would be a good start here. We also need more effective implementation of competition rules. The fact that Facebook was allowed to buy WhatsApp and, it appears, Google will be allowed to buy Fitbit shows that we have a long way to go.”

So, we should not be just hoping for this miracle to happen. Now is the time for action. “The problems, whether hate speech, misinformation, or conspiracy theories are real and they have real-world consequences. In 2020, it is time to grow up and treat them like the real problems they are”, states Joe. In his opinion, it’s necessary that politics interfere in the problem. Joe: “We need to start with implementing the laws that we have, in particular privacy law and competition law. In Germany, Facebook has fully respected the transparency obligations under the German “network enforcement law” (NetzDG), although there is still some work to do there. The NetzDG puts an obligation on big social media companies to allow users to report content as being illegal and to publish records of how much content was found to be in breach of what laws. NetzDG is a long way from perfect or complete, but it shows that legal measures can work when years of ‘voluntary’ measures have not. This means that political leadership is essential, rather than endless rounds of failed ‘self-regulation’.”

Over the next two years, the Expert Committee that Joe is a part of will prepare guidelines on content moderation for member states, to help them address challenges that are vital to our democracies. Joe: “It is politically easy to shout ‘Facebook should do more’ and easy for Facebook to announce that it has removed ‘more’ content, as they often do. The biggest challenge is to inspire some political leadership. This means requiring more transparency from big platforms regarding what unwelcome content is amplified for business reasons, requiring third-party checking of the accuracy of takedown decisions, disincentivizing the making of malicious complaints against certain content, introducing mechanisms to abandon self-regulatory content restrictions that are not working, and so on.”

The guidelines will focus heavily on transparency and cover issues such as problem definition, data collection, key performance indicators, and review mechanisms. In March 2021, the Expert Committee will be finished preparing those informal guidelines for member states. After that, a somewhat broader and more formal document, the Committee of Ministers Recommendation, on the impact of digital technologies on freedom of expression will be published. Such Recommendations are often used by the European Court of Human Rights as a basis for their decisions. Because social media platforms must be places that respect all users rights and freedoms, the Recommendation is drawn up as democratically as possible. Joe: “Everyone is welcome – and encouraged—to take part in a public consultation on the proposed Recommendation next summer. I can say from experience that every single response is carefully read by the Expert Committee members that are leading the drafting process and are genuinely taken into account. I think it is quite exciting to know that anybody can play a real role in shaping such a document.”

Be part of the change!

If you’re interested in contributing, all documents, including meeting reports and some drafts are published on the Expert Committee web page. You can also stay informed by following the Council of Europe’s legal division’s work on Twitter or on the Expert Committee’s web page.