In the age of double tapping, 15 second stories, and infinite scrolling, Instagram’s influence on the museum experience seems undeniable. Many of the articles addressing this influence are focused solely on the negative effects of the ‘selfie-obsessed’ behaviour of the twenty-first century museum visitor—stressing the dangers of selfie sticks, discussing the increasing number of visitors that only look at artworks through their phones, and analysing the risk of the survival and proliferation of only the most visually attractive artworks. In my opinion, Instagram is certainly not “killing museums” but it’s definitely changing the way we look at artworks, experience exhibitions, and visit museums. In this short essay I will shed light on the ways in which museums and their visitors make use of Instagram and the impact this growing social media platform has on the art world. Can the fleeting art of Instagram disrupt the monolithic museum?

Pics or it didn’t happen 🤳🏽

According to journalist Sam Eichner, the act of Instagramming museums and the presence of museums on Instagram “are the natural evolution of art in the digital age – of a society who experiences a thing as much through the thing itself as the Instagram of the thing.” But why would you take a photograph of something that has been photographed probably hundreds or thousands of times before, save it in your camera roll, or put it on a social media platform? The answer partly lies in social media’s culture of validation, the brief rush one can experience while receiving likes or positive comments. Posting a selfie with a Koons, Kusama, or Warhol serves as evidence. It is not just a souvenir of an experience, it is part of the construction of an online identity.

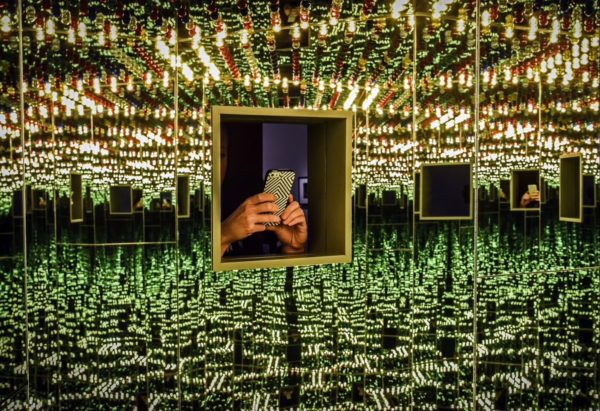

So which artworks feed into the culture of validation the most? What we often see, is that artworks that allow the viewer to be included in the image, through interactivity and reflective surfaces like mirrors, are very popular on Instagram. Immersive and monumental installations score well—like, for example, the meters high Swimming Pool (2016) at Museum Voorlinden, where visitors can photograph themselves within the illusion of being underwater. Another good example of this is Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms, a series of kaleidoscopic spaces consisting of endlessly reflecting mirrors and multicolored lights, dots, or sculptures. One exhibition of her work, at The Broad in Los Angeles in 2017, had visitors waiting in long queues for the opportunity of spending a mere 30 seconds in each installation—and, of course, capturing it on camera.

Is it just because of its immersiveness that Kusama’s work is so hugely popular? Maybe not. Kusama’s 1966 contribution to the Venice Biennale was called Narcissus Garden, a piece comprised of fifteen hundred mirrored spheres, and the artist herself dressed in a gold kimono. Marin Sullivan has pointed out that, “[taken] collectively, these images of Kusama and her work create a complicated amalgam of self-publicity and effacement, presenting a complex fusion of artist, image, and object.” Art historian Jody Cutler sees “narcissism [as] both the subject and the cause of Kusama’s art, or in other words, a conscious artistic element related to content.” One could argue Kusama’s work was not just made for selfies, but its inner workings poignantly reflect on, and critique, precisely the culture it, fifty years later, has become popular in. With “her work being hashtagged more than 300,000 times [on Instagram] and with Katy Perry, Adele and Nicole Richie all seeking out one of her famous Infinity Mirrored Rooms for a selfie”, perhaps the reason for Kusama’s work being so popular has less to do with its visual attractiveness after all, and more to do with its content.

#Empty 📸

While visitors might receive cultural validation from posing with a particularly Instagrammable work, museums, in turn, benefit from the promotion of their exhibitions and collections through Instagram posts—using them as a kind of free marketing tool. The act of documenting an exhibition has, historically, been controlled and institutionalised—with only professional photographers being given access to document exhibitions. Currently, however, exhibitions are being documented by millions of people from all over the world in their own personal manner on social media. In 2013, museums in the United States started a movement under the hashtag #empty and invited Instagrammers, after closing hours, to come and take photographs in the museum, without being “disturbed” by the presence of other visitors. The Netherlands quickly followed, with the Rijksmuseum, Boijmans Van Beuningen, and Museum Voorlinden organising meetups for Dutch Instagram fanatics—those with accounts with anywhere from a thousand to several thousand followers—that resulted in unique, personal documentation of exhibitions and collection presentations. By sharing the pictures on platforms online, users can share, and publicly reflect on, their personal encounters with art. Through platforms like Instagram, art is introduced to an even larger audience, including people that normally wouldn’t visit a museum, potentially democratising who does and who doesn’t have access to art.

It’s not exceptional for museums to join forces with Instagrammers, not only as a marketing tool but also to give stage to people from outside the museum within the museum’s online narrative. In 2018, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen gave Dutch photographer Lara van der Heijden the opportunity to document the Gelatin exhibition on the museum’s Instagram in her own quirky way and the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam asked fashion collective CFGNY to take over their entire Instagram account for twenty-four hours, resulting in an overload of their imagery on the carefully curated feed of the Stedelijk.

Museums have also responded in another way, namely by creating selfie-worthy spaces and artworks. These selfie spots can range from immersive artworks, like the Barbara Kruger installation in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam—which is one of the most Instagrammed artworks of the museum—or can consist of carefully created visually attractive spaces, like the 3D Roy Lichtenstein room in the Moco museum which invites visitors to photograph themselves in it.

This development has perhaps inspired another trend, the expansion of the ‘instagrammable’ artwork into entire ‘museums’ being built purely for the purpose of creating ‘likeable’ content for Instagram, such as the Museum of Ice Cream in in the United States or, closer to home, Dutch influencer Anna Nooshin’s ambition to open the most Instagrammable museum in Europe. This new genre of Instagram worthy museums (if we should call them museums at all) is filled with spaces that look like art installations and exhibitions constructed to lure in visitors whose main objective it is to share photographs on their social media platforms—a so called made-for-Instagram experience. This development raises interesting questions about whether these spaces hold the same meaning for Instagrammers as more traditional art spaces do.

Keeping up with the critics 🙋🏽♀️

It’s not only museums that are starting to participate in the tile-patterned, short story world of Instagram. Other art related fields such as art journalism, criticism, and history are also following the trend—untethering themselves from traditional mediums like newspapers, journals, and books. Local and international Instagram accounts that devote themselves solely to contemporary art and museums, like @galeriereporter, @kunstkijken, @kunstmeisjes, @allesiscultuur, and @dutchgirlsinmuseums, are multiplying as we speak. Through their use of visually attractive posts and captions that are accessible, mostly non-academic, and not extremely critical, these accounts have the potential to connect a broad audience with art and museums.

Disrupting the realm of art criticism, Gabrielle de la Puente and Zarina Muhammad write about art, galleries, and museums with their collaborative identity The White Pube on Instagram (@thewhitepube), Twitter (@thewhitepube), and on their website. They review exhibitions with brutally honest personal reactions in Instagram stories and on Twitter, and rate them in emojis. Merging art history and pop culture, by seeking associative and visual parallels between the two, TabloidArtHistory (@tabloidarthistory) can be summed up by their Instagram bio: “Because for every pic of Lindsay Lohan falling, there’s a Bernini sculpture begging to be referenced.”

Addressing those that have been historically left out of the art historical canon, Instagram accounts @thegreatwomenartists, @theartherstory, and @artgirlrising dedicate their feed specifically to the works of women or women identifying artists. In an interview, Katy Hessel, founder of @thegreatwomenartists, states that “Instagram is a free online gallery where artists can launch their career and this allows women to thrive, due to the support network of other female artists online, but also because there are so many brilliant ones out there.” What these accounts have in common is that they reflect many museums’ shift in thinking about diversity and inclusion. It will be interesting to see in what ways these Instagram accounts will substantially impact and address structural inequalities, and unequal representation, within the art world.

Perils and possibilities 🔮

Instagram offers a lot of opportunities for institutions, with its potential to connect a larger and, if done with care, more diverse audience with the museum, its exhibitions, and artworks. Instagram can be a space for museums to create and give stage to voices and practices that are normally not visible in the dominant narrative, as the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam does with their series introducing a variety of museum employees on their Instagram (@stedelijkmuseum). As with other historical shifts in the mediation between an artwork and a visitor, like the introduction of the audio tour in the 1950s for example, technology can be a valuable tool and a beautiful addition to traditional ways of looking at and experiencing art. However, museums giving space to, and including, other voices on platforms like Instagram is only a starting point. If the art world really wants to push for change within the traditional institutional system, temporary Instagram takeovers and ephemeral stories are not going to cut it. Real inclusion and diversity comes from structural change and should have effects on the museum’s collection, its permanent employees, and its partners.

Follow for follow, like for like 🥰

Instagram can be seen as a reflection of our cultural citizenship and of shifts in thinking about art and museums. This essay aims to shed a light on the ways in which Instagram is used as a marketing tool, as a form of cultural validation, and as a platform for perspectives and voices operating outside, and on the periphery of, the institution. The social media platform provides opportunities for expanding the boundaries of art criticism and museums themselves, and opening up discussions around inclusivity, diversity, and the art historical canon. There are still many questions that need to be asked and themes to be explored within the coming years. What influence will Instagram have on exhibition design, curation, and documentation? Will the ‘made for Instagram museums’ alter our relationship to traditional museums and exhibition spaces? Although Instagram feels ubiquitous within art and culture spheres, it is still a fairly new platform whose deep, permanent, and ongoing impact is still unfolding. For now, we need to remain critical towards Instagram as a marketing tool and museums built solely for Instagram, while still embracing the possibilities for disruption and democratisation that the platform offers.

✨ This is the second in a series of seven commissioned essays for 2019. With these original essays, our aim is to publish work that engages with digital visual culture, both in its niche manifestations and within the technological, political, and mainstream reality of the internet.