A balaclava-clad insurgent hitches a ride across the desert landscape of Takistan: “I grew up in the slums of a village close to here, before the UN came and took all the resources and raped and murdered our women and children…We need to find some powerful friends that can help us get guns.” In the online world of Takistan, a fictional Central Asian country found in the multiplayer game ARMA 3: Takistan Life, players can choose to take on the role of civilians, the military, insurgents, or even terrorists. In a 15-minute-long video uploaded to YouTube that documents the gameplay, I was struck by how the gamer behind the insurgent, played and voiced by someone from the comfort of his home, managed to never break character, constantly improvising in all sincerity his avatar’s identity. These games provide an emotional reality to the War on Terror construct, allowing us to inhabit both victim and terrorist. But what can the participation in terroristic gameplay and its imagery suggest for our identity and our sense of meaning? Are these merely games, or are these images part of a larger economy of symbols that are taken up by both real and hyperreal terrorists?

Terrorism in games

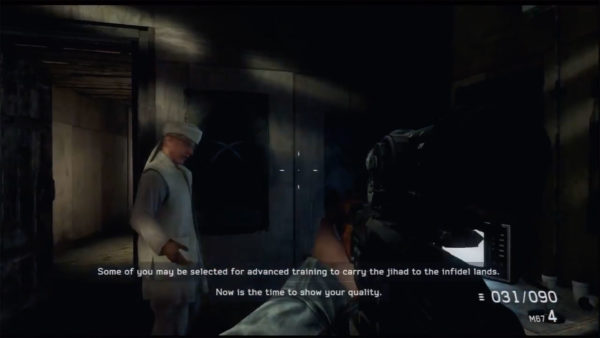

Since 9/11, video and computer games have increasingly allowed us to play as terrorists. As popular Western media reinforces the Us-vs-Them narrative that emerged after 2001, video games have followed suit, offering back to us virtual realities of the War on Terror that pits the West versus Islamic fundamentalists. At first, these games failed to deliver any meaningful opportunities to play as a terrorist, often anesthetizing the role by setting up the character as a ‘double-agent’ or ‘infiltrator’. But progressively, games like Grand Theft Auto, ARMA 3, Insurgency: Sandstorm, and SQUAD began to provide for surprisingly subjective explorations of terrorist roleplaying, where “the video game avatar, presented as a human player’s double, merges spectatorship and participation in ways that fundamentally transform both activities”.

In my short film Aim Down Sights (2018), I explored the experience of this roleplaying, both as victim and as terrorist, and the dedication of those playing to these online identities. In numerous videos that have been uploaded to YouTube over the past few years, historical acts of terrorism are re-enacted, from specific events like 9/11, London’s 2005 metro bombing, and the 2015 Thalys train attack, to more general events like airport shootings, plane hijackings, and vehicle-pedestrian attacks—all of which now form part of our general image of terrorism. Some of these roleplaying games offer opportunities for people to invest time and energy into the characters they control, forging identities that require long-term negotiation. Here we find gamers fully committed to playing as a terrorist, developing their own in-game backstory for their character’s radicalization, justifying their motivations to other players, and engaging in acts of terrorism.

The appeal of terroristic images

Where does this desire to roleplay terrorism come from? Perhaps it is a way of coming to terms with a 21st century narrative that reinforces the spectre of Islamic fundamentalist terrorism as the menacing Other, or a way of working through the media images of terrorism that are now so ingrained in our collective imagination. In one video, a gamer explores the ruins of a terrorist-destroyed skyscraper. “This is horrible…it can never be put up again”, he grieves as he dwells on the virtual destruction. Or perhaps it allows us to explore the socially transgressive acts of terrorism in a zero-consequence setting in what amounts to “just a video game”.

Nonetheless, the endless re-creation of terrorism in gaming reminds us of the seductive power of its image and its visual realm. It is at once captivating and horrible. Here is our inability to look away; our direct confrontation with the real in a society permeated by simulation. In his 2016 documentary HyperNormalisation, Adam Curtis edits together a series of clips from nineties films where citizens of cities gaze upward toward an incoming disaster. Mouths open, they stand paralyzed before off-screen spectres that threaten to annihilate them: comets, monsters, aliens, terrorists, or any other terrible Thing. These clips are followed by cuts of buildings being destroyed, Manhattan in flames, or the White House exploding. The implication is evident: the desire for the real—this larger-than-life experience—is palpable in our media, and has paved the way for our fascination with the spectacle of destruction we have found in this century’s terrorism. But what are the consequences for a society that, as Curtis shows, primarily understands itself through images and through heavily mediated experiences?

It is important to reinforce that the empirical violence of terrorism is obvious and outside the scope of this article. What is at stake is terror’s symbolic power over us through our consumption and reproduction of its image in video games. Unlike other violent games, terrorism implies not only a very specific kind of identity, but an entire reality of symbols, of geopolitics, of historical social narratives, and of real-world politics that play out in the present. This is what makes terrorist gaming markedly different from any other violent game play. We can no longer talk about violence, emptied of signifiers, enjoyed for its own sake. There is something immediately unsettling about playing a game that allows you to choose as your weapon a suicide vest. Nor do we have the historical distance to neutralize its meaning. When we roleplay terrorism, there is a certain complicity between our online selves and the Us-vs-Them narrative we begin to co-author along with popular media.

Roleplaying, identity and reality

When we roleplay online, we invest a certain amount of identity into our online avatar. The avatar can itself become more than a symbolic stand-in. It can become an ontological extension of the self. In a much-discussed case, Carmen Hermosillo (aka Humdog) wrote extensively on her experience of online roleplaying and its effect on her personal life. The psychological experience she had through her avatar’s romantic relationship with another character in Second Life, a popular online virtual world, eventually took a dark turn. After deleting her avatar, she took her own life in 2008. While this is an extreme case, Hermosillo provided a very self-aware account of how the personal and online identity can become blurred through roleplaying, as well as how one’s reality can be transformed. In her research into gaming and roleplaying, researcher Marinka Copier describes the online personality as a series of unstable “roles and frames [that] can never be fixed because they are continually being negotiated and (re)constructed” into new ways of being. So what does it mean to reconstitute oneself into a virtual terrorist?

The magic of roleplaying in gaming lies in the chance to explore characters our daily lives don’t permit. It’s not that a gamer truly believes themselves to be a character—what has been called an “immersive fallacy”—but much like in reading, a certain kind of emotional transformative experience is made possible. In the case of roleplaying terrorism, what is at stake is not the gamer’s transformation into a terrorist (ISIS explicitly used video games as a recruitment tool, but were successful in recruiting only about 3% of gamers). What does matter is the emotional investment into terrorist roleplaying. For the individual gamer, the constant replaying of terroristic events verges on their ritualization. Through their incessant repetition, these virtual worlds we inhabit are bestowed a symbolic value. In other words, they enter into the economy of symbols, meaning, and experience that have value not only online but also in the world. We must consider that emotional participation is very much an affirmation of its meaningfulness, or in this case, the affirmation of the value of the virtual desert-war space. In another online video, a gamer defends himself: “This is a video game so this is not aimed at any particular event that’s happened in real life. Anything like this is absolutely horrible in real life…but in the game scenario…it’s actually quite fun to do.” Indeed it is, but we must also consider the constant negotiation between the personal identity and an ever-increasing way of understanding one’s identity as it is produced and reproduced in the world.

The blurring of realities

While the subject of terrorism is finding its way into gaming culture, gaming culture has already found its way into terrorism. Head-cam videos of jihadi soldiers going into battle are available online. These videos borrow heavily from first-person shooter (FPS) visual language. It’s not merely the first-person perspective that they share; jihadi soldiers pick up and cycle through weapons as you would in a game, kill-shots are slowed down and replayed, and voice overs mimic ‘kill-count’ praise typical of games. Our familiarity with FPS games allows these GoPro video uploaders to tap into our established gaming sensibility. What we end up with is a bizarre exchange between terrorist image-making and popular culture, where both freely borrow from and reinforce each other. The appropriation of gaming language begins to create an uneasy indistinguishable aesthetic that blurs these two opposing virtualities.

The recent shooting in Christchurch, which led to the death of 50 people, provides a disturbing illustration. As Kevin Roose wrote for the New York Times, what was startling about the shooting was its live-stream format and “how unmistakably online the violence was, and how aware the shooter on the video-stream appears to have been about how his act would be viewed and interpreted by distinct internet subcultures.” What emerges is an exchange of a visual language, and a new lens through which the “real” plays out.

When the live-stream was shared on Facebook, the social media company came under attack for failing to prevent the video from spreading. But Facebook, relying on AI-trained automated filters, admitted that the video couldn’t be discerned from “visually similar, innocuous content”. Facebook’s head of integrity argued feebly that “if thousands of videos from livestreamed video games are flagged by our systems, our reviewers could miss the important real-world videos where we could alert first responders to get help on the ground.” What happens when what we do online and what is done in the real world becomes indistinguishable, or when this all too “real” is played out again and again as entertainment?

Erasure through immersion

The significance of these virtual worlds and images must be understood through the meaning they provide society. When our reality becomes mediated through images, those images themselves begin to be the source of our orientation to the world. As we move deeper into aesthetic representations (i.e. virtual and augmented reality) and subjective experience (i.e. immersion, connectivity, participation) we are bringing about a unique moment in historical iconography, or image-making, where the image takes precedence over the lived experience. What can it mean to create entire worlds based on terrorism, and the emotional experience of terrorism, when it is these worlds that begin to occupy more and more of our daily consciousness and experience of self?

As immersion increases, the distance necessary to critically engage with the subject matter may be jeopardized. This is why terrorism in gaming may be not so much an opportunity to reflect on terrorism but to affirm its visual and emotional power over us. No doubt the immersive reality of virtual terrorism will become ever more real as AR/VR technology improves, but our thinking of terrorism will likely not improve with it. Simply put, the complexities of terrorism (its politics, its image, its significance) remain blurry while its aesthetic representation becomes more vivid. We already know that gaming doesn’t lead to violence, but it can lead to its visual and aesthetic normalization as well as its roleplaying legitimization.

About Salvador: Salvador Miranda (1987) is a Canadian artist based in Rotterdam. His work explores emerging realities produced by new technologies, online communities, and the digital image. In particular, his work focuses on the inherent ideological tension found in the images we consume and our visual affirmation of them. His current artistic research explores the political implications of image-making in popular culture. Salvador is also the Development & Research Coordinator of the Living Architecture Systems Group; an international consortium of researchers, artists and scientists applying experimental and artistic practices to speculative architectural design. His production work includes exhibitions and collaborations with international artists and institutions.

✨This is the third in a series of seven commissioned essays for 2019. With these original essays, our aim is to publish work that engages with digital visual culture, both in its niche manifestations and within the technological, political, and mainstream reality of the internet. Want to be the first to know when our next essay is published, stay up to date on our activities, or just find the latest ‘must sees’ on the internet? You can have all that and more when you sign up for our newsletter!