Nicola Bozzi is a freelance writer and PhD student at the University of Salford, Manchester. His research deals with social media tagging, identity, and the globalisation of stereotypes. These are the images he encountered this month and he’d like to share with you:

“Since his first YouTube hit Gummo (it was only 2017) Bushwick rapper 6ix9ine aka Tekashi69 has skyrocketed to worldwide fame. However, the rapper is falling just as fast as he rose: after being sentenced to 4 years probation for filming a sexual performance by a 13-year old, the rapper is waiting on a racketeering sentence that could cost him life in prison.

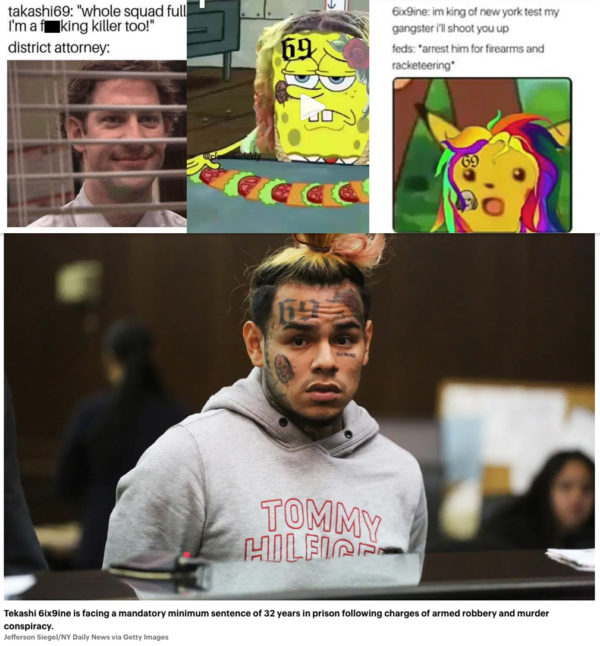

Throughout this brief parable, 6ix9ine has been constantly memed: not only was it a meme that made him famous to begin with, but his rainbow styling keeps going viral throughout his dramatic fall.

Beyond the novelty factor of his gangsta-anime aesthetics, however, these is a less frivolous aspect to his Internet fame. As it often happens with artists that are embedded in gang culture, the frequent public testing of 6ix9ine’s street credibility on social media has played a big part in the spectacle offered to fans and haters in the form of viral clips. Despite warnings from older and more experienced artists, Tekashi’s lack of control over his gang environment eventually combined with the scrutiny instigated by his own success; as a result, his career seems to have been cut short in much the same way as it happened to the similarly young and Internet-famous Bobby Shmurda.

Gangsta rappers have had an ambiguous relationship with their criminal surroundings since the dawn of the genre in the late 80s – early 90s, but while their role is usually understood as akin that of a writer reporting the reality of certain socio-economic conditions, real-life beefs often follow diss tracks and artists may become victims of their own credibility.

Reputations being at stake, the evolution of media has proven crucial in the evolution of beefs and the dramatisation of the gangsta: as demonstrated by research in the gang-heavy South Side of Chicago (also the hometown of drill music), in the age of social media the pressure to “keep it real” moves from musical tracks to Instagram stories, Twitter feuds and Facebook humiliations, which in certain contexts often spiral in real consequences. Gang violence is thus accelerated, amplified, and promoted on social platforms, where entire ecologies of re-post accounts, stories compilations, and beef histories are collected to harness clicks and perpetuate damage. Another study on the context of South London has shown that the bigger the audience, the bigger the chance of retaliation – a point that highlights the responsibility of platforms themselves in terms of providing adequate and anonymous moderation tools.

The memes above are thus more than ironic jabs at a celebrity: they also reflect the voyeuristic nature of social media and how quickly the globalisation of images alienates audiences from the material conditions in which their subjects live.”

“I posted this picture on Facebook a few years ago and I got the most thumbs up in my 10+ years of existence on the platform. The formula – single figure facing the horizon, exotic landscape with no other people in it – is a common trope within the aesthetic of the digital nomad. This figure has existed since the late 90s, as soon as consumer technology became small and powerful enough to allow for remote work, but somehow it has gained more mainstream traction in the last few years.

Apart from (not so) secretly wishing to be a digital nomad myself, I’ve always found the contradictions embedded within this new social media stereotype quite fascinating, not least on an aesthetic level. For example, while remote work is a sustainable alternative to the office grind for a variety of people from all walks of life, the digital nomad is sometimes associated to the “tech bro” stereotype and, in terms of aesthetics, is usually depicted as a (mostly caucasian) freelancer working from a beach-side, Wi-Fi enabled bar in a South Asian country.

I never understood the appeal of working from a beach (it seems, at the very least, impractical), but I think the image does a good job at representing the contradictory tension between a carefree lifestyle and the relentless, compulsive self-branding necessary to achieve it. Unlike the old-fashioned backpacker, travelling on the cheap and trying to collect “authentic” cultural experiences, the digital nomad needs to be tethered to the cloud at all times, often to sell the very lifestyle he or she is attempting to achieve. Social media have of course made us all well aware a little “fake it ’til you make it” mentality is necessary, but in some cases the promise of digital nomadism can manifest in actual scams or at the very least spectacular failures .”

“I’ve known artist @catonacci_official for a while, so I’ve had the chance to witness his rise to Instagram micro-celebrity from its infancy. The story is this: haunted by student debt, this former Marlboro model has been forced to become a cat sitter – a task he performs with a somewhat aggressive attitude and without dropping the old habit for a second.

What I like about this account is the hi-jacking of the #instacat tag as a vehicle for shameless click-bait/downright trolling, a practice that draws attention towards Instagram’s self-promotion dynamics in a satirical way. The mix of real-life snaps and blatant photoshopping is also a South Park-esque reminder of how fictional life on the platform is, but also of the fun you can have with it.

Another reason I find the project interesting is it sits within a long tradition of feline appropriation online. An example is an old campaign by Norwegian Anonymous , encouraging people to spread tampered-with versions of the infamous manifesto written by white nationalist terrorist Anders Breivik in an attempt to defuse and ridicule his message. The version going around at the time, of course, featured a generous amount of LOLcats . Another case was a Twitter appeal by the Brussels police, who asked citizens to avoid sharing information that might expose or interfere with their operations during a lockdown. As a response, the public flooded the platform with a plethora of cat memes.

At the end of the day, cats might be one of the most persistent Internet archetypes because they elicit some kind of empathy within a typically disembodied environment. They can still be very creepy though .”

“Someone in my network posted this picture on Facebook. The tags in the top-right corner are automatically added by Facebook’s image-tagging algorithm and are invisible unless you install this add-on . I recommend doing it, since it offers a useful glimpse into the state of machine learning on a platform that, while losing its market grip on gen Y and Z, remains stable in providing your parents and grandparents with exciting personality tests and fake news.

While social media tagging is something we are all pretty much aware of, image tagging happens in the background and it can be pretty awful. A famous example from a few years ago is when Google came under fire because its new Photos applications tagged black people as “gorillas” , but there are more subtle ones: Facebook had to change its automatic face-tagging setting across Europe after an audit by the Irish data protection commissioner , while its habit to tag some people as “interested in treason” was also frowned upon.

In the image above, however, the algorithm is just mistaking a Christmas tree for a person, which is a somewhat relieving example of what we might call “artificial stupidity “. In case it works the other way around, maybe we can expect Christmas decore to become a fashion trend among those interested in camouflaging from face detection.”